TRADEMARK STRATEGIES FOR THE ENTREPRENEUR[1]Britten Sessions and Mitesh Patel contributed to this article

Choosing a Trademark

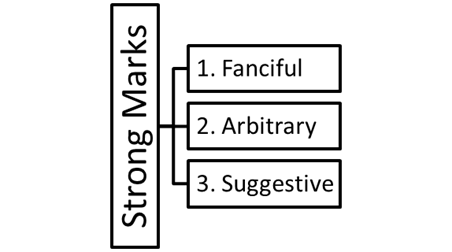

Trademarks identify your brand. They set you apart and can provide a competitive edge when properly utilized. The potential strength of a brand, whether it be used to identify a product, service, or both, is an important consideration for any business when choosing a name. The stronger your trademark, the easier it may be to protect, and use to your advantage. When thinking about trademarks, it is important to consider what can actually be protected as a source/brand identifier – there are “strong” marks, which are inherently distinctive, and “weak” marks, which are descriptive or generic. Think of the strength of trademarks as a hierarchy of five categories split amongst strong and weak marks. We’ll start at the top – the “strongest” and work our way down to the “weakest” types of marks.

A. Strong Marks

When I say “strong,” I don’t mean how catchy it is, although that can help (more on that later). A mark that is fanciful, arbitrary or suggestive is inherently distinctive, versus a mark being capable of acquiring distinctiveness (descriptive), or a mark incapable of acquiring distinctiveness (generic) and as such, unprotectable.

1. Fanciful Marks

Fanciful marks are inherently the strongest type of mark. Under this category are marks and words that have been invented for the sole purpose of functioning as a trademark. These words are not found in the dictionary (at least at inception), do not have a translation in a foreign language, and are not intentional misspellings of words. The typical examples are “KODAK” or “XEROX”. These words have no other meaning than those we as consumers have attributed to the products or company associated with them. Prior to the inception of these brands, the words had absolutely no significance to consumers.

2. Arbitrary Marks

Arbitrary marks also make strong trademarks and are composed of words which are known to have some meaning, compared to fanciful marks which are often made up words. However, while these words can be found in the dictionary or be translated into English, they have no connection to the good/services. Arbitrary marks use common words but apply them in an unfamiliar context. For example, while “APPLE” is known to be a fruit (and any such foreign equivalent such as MANZANA), from a brand perspective, consumers would associate the name with the multinational technology company. If Apple Inc., makers of the iPhone, iPad, iPod, etc. instead went into the orchard business and sold fruits and vegetables, the trademark would be descriptive or generic as explained below. Instead, the adoption of APPLE as a trademark (and the iconic “bitten apple” logo seen below), is arbitrary when applied to their products as it has no actual connection to their offerings.

3. Suggestive Marks

Suggestive marks can toe the line between making a direct connection between your mark and the associated product/service and still be protectable. Suggestive marks require some imagination, thought or perception by the consumer to reach a conclusion as to the nature of the goods. I love a good suggestive mark – one that makes you think twice and smile when you make the connection between the mark and the good/service. These marks should not literally describe the goods or services, or it is going to end up being a weak mark. Common suggestive marks include “GREYHOUND” for bus services (suggesting that the bus service is fast like greyhound racing dogs), “MUSTANG”/”JAGUAR” for cars (alluding to similar characteristics), or “COPPERTONE” for suntan products.

A suggestive mark may not be as inherently distinctive as one that is fanciful or arbitrary, but from a marketing perspective, it can actually be better when done right. You may prefer a suggestive mark to a fanciful or arbitrary mark because a suggestive mark plants a seed in the mind of your potential consumers as to the nature of your offerings while still being able to provide trademark protection. These marks may be easier to build a brand around because unlike arbitrary or fanciful marks, there is some connection with your goods or services, and thus will require less advertising and marketing expenditures to build brand awareness. However, choosing a suggestive mark can be difficult as something you may think to be suggestive may be descriptive to someone else and thus is our weakest “strong” mark as these marks are able to walk the line on the strong side.

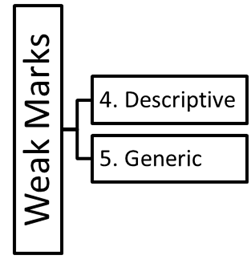

B. Weak Marks

Too often I encounter business owners seeking to stop competitors from using something similar to their trademarks, only to find they don’t quite understand how trademarks work. Sure, you started using the name first. Sure, your product/service is more popular. But, you’re trying to stop someone from using a generic or highly descriptive term, which is incapable of functioning as a trademark (to identify your brand in particular over others). Don’t let this be you.

If a mark you really like isn’t fanciful, arbitrary or suggestive, don’t give up just yet. It still may be capable of protection, even though it is a “weak” mark. Possibly.

Weak marks can be great – don’t get me wrong. There are plenty of marks that would be considered weak, but are dominant household brands that we have come to understand as pointing specifically to the trademark holder. But that’s just it – it takes time and effort to enforce a “weak” trademark, and not all weak marks are capable of being protected. Let’s take a more detailed look.

1. Descriptive Marks

Descriptive marks are those that in some way describe (even a bit) something about your goods or services. If someone looking at your mark can tell something about the ingredients, quality or characteristics of what you provide, it may be deemed descriptive. Within this category are marks that are geographically descriptive, surnames, or functional in nature.

2. Generic Terms

Generic terms (note these aren’t even considered “marks”) are those which are common names for the product or service. A generic term (“COLA” or “POP” for soda) is incapable of acting as a trademark because the whole point of trademarks is to distinguish yourself from others. Generic terms are afforded no protection and cannot acquire distinctiveness. Be careful though, marks can become generic over time. Many people think “KLEENEX” any time they see a tissue box, or likewise “BAND-AID” but these are brands and in an effort to make sure they don’t become generic, owners will encourage proper use of their trademarks and refer to them as brand.

I understand the desire to use a trademark that consumers can encounter and easily understand what you do or where you’re located. For one, it is easy to market – you don’t have to go through all that effort in trying to get some coined phrase or made up word to catch on and then relate back to your business, but therein lies to dilemma. Nothing good comes easy, and marks that serve merely to identify the nature, location, quality, etc. of your goods/services are those that others conceivably may need to use to use to merely identify their own offerings. Such words or phrases can become strong if you police them and use them properly, but again, this takes time and effort.

Does the name you want to trademark for your mobile application describe, even in the least bit, some function of your app? Even if true to a small extent, the other robust offerings of your app may not be enough to drag you out of being descriptive. The idea is that everyone should be allowed to use words that merely describe their goods or services, describe the origin or have some geographical reference to the offering, or are recognized as common surnames. However, these descriptive terms are capable of acquiring distinctiveness – that is, while not inherently distinctive like fanciful, arbitrary and suggestive marks, can become distinctive through usage and/or acquire secondary meaning. Before we get to how one acquires this magical “distinctiveness,” let’s take a look at some potential pitfalls within this category, namely, misdiscriptive or deceptively misdiscriptive marks.

Let’s say I make watches, and I just can’t come with something fanciful, arbitrary or suggestive that I like. I do some brainstorming, and think of what I want my brand to embody. I recall that the Swiss are known for their precision time-pieces, so I’ll call my brand “Swiss Watches” (wait, isn’t that already a thing? Putting that aside for now…) – bravo! I’ve come up with a trademark.

My trademark has two words in it – SWISS and WATCHES. “Swiss” is geographically descriptive as it is clearly alluding to Switzerland and I’ve added the generic term “watches” which we know won’t help me. However, my watches have nothing to do with Switzerland except that I want people to think of Swiss efficiency when thinking of my products. Are my products efficient? Well sure, I’d like to think so. Is that enough? Probably not.

Do my watch designs come from Switzerland? Are my watches produced or manufactured there? Is there any connection to that beautiful country? Well, aside from the fact that I may really want to visit, if there is no real connection between my offerings and the geographical location, my trademark may not only be weak, but it may be deceptively misdiscriptive. I want people to think about the embodiments of Swiss engineering when they think about my watches, hence the name, but my products have nothing to do with Switzerland.

How would you feel if I tried to sell you some Havana Cigars TM)? You may only purchase the cigars because they indicate a well-known geographical location (Havana, Cuba), which also happens to be known for producing high quality cigars. On finding out that the cigars I sold you at a premium had nothing to do with Cuba, but were made in Wisconsin, a consumer would be justifiably upset. Trademarks aim to reduce consumer confusion while allowing owners to distinguish their offerings, and as such, misdiscriptive marks may not be eligible for protection.

Take it one step further – I really want the trademark “100% Organic Hand Rolled Cigar!” First, my cigars must be 100% organic, and they must be hand rolled. If either of these are untrue, my trademark is deceptive. Second, this slogan is very informative in nature – there can be several other manufacturers now (or in the future) that may utilize 100% organic ingredients and may be hand rolled and such manufacturers would need these words to merely describe to consumers what their product consists of (quality and ingredients). As such, this again, would not only be a weak mark, but potentially incapable of functioning as a trademark as it merely informational.

C. Consistent Branding

You’re ready to start your business, or have just thought about getting ready to protect some of your intellectual property – now you have to figure out what is protectable and how you want to execute your branding strategy. This is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Branding will vary widely depending on the type of business and what specific types of goods and services you offer. Even then, branding can be widely divergent within similar industries and creating a uniform branding regime is key to reach relevant customers.

First, you want to think about what monikers, symbols, phrases or other source identifiers you use that distinguish your business from your competitors. How do your customers differentiate you from others who are offering similar goods or services? The simple place to start is your letterhead or website – the header of your website (not necessarily the domain) is what your customers will know you by. If they are one in the same (Amazon v. Amazon.com), then great – looks like your trademark in that case would be AMAZON. However, if your header is CARS.COM (as well as your domain – see www.cars.com), then that will be your trademark.

Thinking of your header v domain name is a great place to start if you haven’t done so already – but keep in mind that you want to use this same design/verbiage on all your materials. This includes your terms of service or privacy policies if applicable, letterhead, newsletters, business cards, and websites. In short, STAY CONSISTENT. This includes designs, if you are utilizing any, as well as colors.

Trademarks are very particular in the form of protection offered – you must use the trademark consistently in the same way. Generally, top level domain suffixes (.com, .info, .org, etc.) are going to be generic and not distinguish your trademark from others. I hesitate to use the cars.com example, because based on the foregoing section, you might think, “isn’t cars.com a generic trademark! If cars.com can have a registered mark, why can’t I register my mark that you said was generic?” Well, first off, you may get protection for specific designs, but may have to disclaim any wording that is generic (entity designations also fall into this generic category, such as LLC, INC, Corp, Partners, etc.). In which case, you’ll really only have protection for the color/design and while the words are included in your trademark, you may have a hard time stopping others from using parts of the words within your trademark if it is deemed to be descriptive/generic.

Next, think about any slogans you use. Punctuation matters. If you’re using a slogan or phrase that customers will associate with only you, you may want to think about protecting those slogans as well. Keep in mind that stringing a bunch of informational words together may not be enough to take you out of the descriptive realm, or the Trademark Office may consider your slogan just that – merely informational, and thus incapable of functioning as a trademark. This just means that when a consumer sees your slogan, it does nothing to identify the source of the product/service and merely provides information about the services. An experienced trademark attorney can help figure out if your slogans are protectable. Again, use these consistently on your advertising/outreach materials – the longer you use them, the more likely you may be able to garner some sort of protection for these marks by acquiring distinctiveness in the minds of consumers so that they relate purely to your company and endeavor.

Take a look at a trademark that was filed for the provision of natural gases – “ALL PROPANE IS THE SAME, OURS IS CHEAPER!” This trademark at first glance seems to be merely informational, and in fact, that is exactly what the Trademark Office indicated. However, the applicant was able to show that he had used the trademark for over a decade and in that time, embarked on an extensive marketing campaign, complete with newspaper and magazine adverts, billboards, radio spots, using it on letterhead, etc. to the point where he had an outpouring of customers willing to declare that when they saw that phrase, they associated it uniquely and unmistakably with the applicant. The Trademark Office relented and granted the applicant registration of this trademark after some back and forth and dozens of declarations and evidence from the relevant class of consumers that encountered the mark.

Consistency is not only important in expressing your brand to make sure customers will always think of you when they see your marks, but crucial to legally maintaining your brands. The less distinctive your mark is, the more likely inconsistent usage can eliminate any rights you acquired.

If you’re protecting a specific design, keep in mind that fonts and colors are important. My nephew can’t read, but when we walk down a supermarket aisle, he knows exactly what a Coca-Cola bottle looks like and will demand a Coke. Without thinking too hard, you can easily think of the iconic red background with white cursive lettering spelling COCA-COLA. Coke knows what it’s doing by keeping things consistent, ensuring that generations of people recognize its logo from a distance. Just think if other soda makers used the same colors/font and how confusing that might be to the toddler who can’t quite read and somehow purchases an inferior competing product all because he was confused! This example is obviously overly simplified, but the tenet applies to your business just the same.

D. Logo, Word Mark or Both?

To start the discussion of what you should be protecting in terms of a logo/design or word mark, let’s talk about the differences between them and what protections apply to each.

1. Word Mark

A word mark, or a standard character mark protects the literal elements (the words) without claim to any specific colors, fonts, style or design. You are protecting only the words and are free to use the mark in any design (consistent with other’s rights – meaning, you can’t just trademark a standard character mark and start using Coca-Cola’s colors and design without running into some trouble), without claiming an exclusive right to any particular design element. Keep consistency in mind – while this does provide broad protection so you can use any color, design, font, etc. that you want, do you really want to do that?

However, standard character word marks can create the baseline of your protection and will let you stop others from using the distinctive words you use in your mark to differentiate yourself from others. To protect a standard character mark, all the letters and words in the mark must be depicted in Latin characters, all numerals in the mark must be depicted in standard Roman or Arabic numerals, the mark can only include common punctuation or diacritical marks, and the mark cannot include any design element.

2. Logo Mark

A logo mark, or a stylized/design mark, is exactly that – it protects the design characteristics, including a claim to a particular font, style, size, shading, and even color if you so choose. You can also file a design mark in black and white if you plan to use different colors on it, as long as the coloring is consistent with the black and white image (e.g. no different shading, unless a gradient is present in the black and white design). However, think again about consistency – while you have some options, from a brand perspective, you want to keep things consistent to make sure your customers continue to recognize your branding and can use it to differentiate between that of your competitors.

Coca-Cola has protected different variations of its logo as well as the standard character mark based on its actual usage, and you should think about doing the same depending on how you actually use your marks. An experienced trademark attorney can review your marks for you and provide guidance as to the best way to protect your mark.

3. Which one to pursue?

Sometimes I will recommend to a client to start protection with a design mark, possibly due to some potential conflicts with the word mark. Keep in mind that the standard character mark casts a broad net in terms of potential conflicts in that similar wording in other marks (even if the other mark is stylized) may be caught as a basis for refusal because when requesting protection for a word mark, you’re basically saying you’re going to use it in any way, which may include the design of someone else’s mark.

As another example, I suggest filing a design mark if the literal elements in a mark just aren’t distinctive enough to garner trademark protection, but the design they are using can be distinctive and has other elements you want to protect (letters in the shape of objects, specific colors, or other design elements that lend themselves to being distinctive versus just the words alone). With this tactic, you may have to disclaim the literal elements from your mark, meaning that while you can’t stop competitors from using the specific words in your mark (cars.com), you can stop them from using the specific design that you utilize if granted (the purple bubble, font, and style of the particular logo). In the Coca-Cola example, the word COLA is generic and Coke can’t stop Pepsi or RC from using COLA, but it can stop others from using the specific coloring, font, and style for similar goods which is key to enforce your intellectual property.

When using a logo, you want to pay particular attention to the creation process – where did you come up with the design? If you hired someone to design your logo for you, make sure you have the rights to the image to file for trademark protection. Look to the contract you entered into with the designer and if you haven’t gotten this done yet, ask the designer to include it into the contract. Also, where did the design come from? Did you free hand it and then have it professionally made? If so, kudos – but keep in mind that even inadvertent similarities to existing trademarks can cause problems. If your logo incorporates stock images, check the license you entered when you purchased the stock image – sometimes these licenses can restrict your ability to file the design as a trademark.

While there may be no restrictions in the license, or if you found an image in the public domain and incorporated it into your logo, be wary of any existing rights or other people doing the same who have already filed for trademark protection for some variation of that image (even if utilizing different wording). In this sense, design marks can also cast a broad net as far as potential conflicts go because there a plethora of issues that come up with design elements are similar to others already out there. For example, even if you use a self-made stylization of two hands coming together for a handshake, the overall design element may be similar to a different clip-art, professionally made, or other logo already filed that could be a conflict if used for similar goods or services. Keep reading for ways you can reduce the risk of refusal of your trademark by having a proper clearance search conducted prior to creating, using or filing your trademark.

Protecting Your Trademark

Now that you’ve figured out what trademarks you want to use to distinguish yourself from your competitors, you should think about creating and protecting those rights. In the United States, you can acquire trademark rights by simply using your trademark in commerce. That’s all well and good, right? Use the trademark, get protected? However, without doing anything further, the risks of losing rights you’ve worked so hard for is a real possibility. You should think about filing your trademark either with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, or file a state trademark.

For our purposes, I’ll be focusing on the former for federal trademark protection. You must use your trademark in interstate commerce in order to be granted a federal trademark registration. This means you must use your trademark on goods and services identified in your application (more on this later) between multiple states within the United States or from within the United States and a foreign country. If you’ve only used your trademark within a single state, you may not qualify for federal trademark protection, but this can vary and you should consult an attorney to best advise you as to the particulars on whether your usage may qualify.

A. Trademark Clearance Search

One of the first things you want to do is perform a trademark clearance search to see if your trademark is already in use by someone else on similar goods or services. I’m going split this in to two of the most common types of searches you can do: federal clearance and common law search.

1. Federal Clearance

One search you can conduct is a search of all federal trademark databases that are available to see if someone is using a similar mark as the one you want protection for. A federal trademark search can be done directly with the United States Patent and Trademark Office as they catalog all federally filed trademark applications. One benefit of starting here is that you can go through all similar trademarks that have been filed. There will be two general categories of marks you will find – “live” marks and “dead” marks. Don’t skip over marks that are “dead” as those can be important to review for reasons discussed below. “Live” marks indicate that the trademark is currently pending (still in the review process or pending registration), and “dead” marks indicate that the application has either lapsed or never completed the registration process.

Just because a mark is “dead” does not mean it is of no importance. I will regularly start a very broad search for the trademark a client has requested without specifying the goods/services or the field of use. This gives us a baseline of other parties that have applied for that term. You want to carefully go through any direct matches and review whether these marks are pending, registered, or dead. Going through these marks can give you an idea of what else is out there using the same name as you want to use.

Dead marks may no longer be valid for a number of reasons that are useful to figure out. First, a mark may be dead because the applicant merely failed to meet some procedural requirement. This could include a request to disclaim some portion of the mark, to clearly define the recitation of goods/services, to properly sign the application or other such reason that the applicant did not comply with resulting in the application being abandoned that otherwise may have been registered through a proper response. Second, a mark may be dead due to a refusal based on a substantive issue, such as a likelihood of confusion, or refusal based on the fact that the mark was non-distinctive or generic. This is important to understand because your trademark could face the same refusal depending on the particular usage. Third, a dead mark may have simply failed to be renewed. This could mean the owner of the mark is no longer using the mark, or that they simply forgot to file the renewal (keep reading for more on this later so you’re aware of the renewal requirements). This could mean the party who filed this mark was successfully granted registration, and while they failed to renew their trademark registration, they are still out there using their trademark, resulting in common law rights that may trump your rights if the marks are similar to yours. It gives you an idea of what else may be out there.

Live marks are obviously more important to go through because these marks are either registered or pending registration and thus could be a potential bar to the registration of your trademark. Some of the pending marks may have been refused or are simply awaiting examination. Again, you want to look through these marks and compare what goods/services these marks are used for. Additionally, it may be helpful to review the prosecution history to see what refusals, if any, were issued, for if they are similar to yours, they could be a basis for refusal if registered (or at the very least could be used to suspend the prosecution of your trademark application until the pending application is either abandoned or registered). In short, if pending marks are similar to your mark, your trademark may be refused. At a minimum, your trademark may face similar issues which you will want to be aware of.

A good trademark search will encompass results that are not only exactly the same as yours, but also those are that are similar, either in appearance, sound, context or commercial impression. Thus it is important to search for phonetic variations as something that sounds similar to your mark, but is spelled differently, can also be used as a basis for refusal. Remember, creative spellings alone may not be enough to avoid a refusal based on a likelihood of confusion, or if your mark is deemed to be descriptive or generic. The Trademark Office will examine your mark as a whole and compare it to other live applications as well as review it to see if there are any other issues before approving the application.

2. Common Law Search

Remember that trademark rights are based on use and thus rights in a trademark can be created based on use. That can be great for you as you may have already begun creating trademark rights if you’ve used your trademark, but this can be a double edged sword as even if you’ve done your due diligence and conducted a search of federally registered trademarks, there may be someone out there who has not registered their trademark federally but whose rights may still be superior to yours. As such, you may want to also consider conducting a search of marks being used that are not registered to see what else is out there.

Common law searches can differ in scope, and I’ve found that most clients will ignore this facet of potential conflict. The difficulty here is that unlike the federal search, there is no single uniform database in which you can search to find a definitive answer on whether there are any potential conflicts. As with the federal search however (and more so with common law results), even uncovering a potential result may not tell you if you have priority/seniority. With the federal search results, there is at least a date of first usage that each trademark application will have, which is only the earliest date by which the applicant began use of the mark (note that it can be before this date as well). As such, when conducting common law searches, it can be difficult to ascertain when usage began for any hits you find.

Google is your friend, but internet results may not be definitive. You may think that putting your trademark name in Google and not coming up with any relevant results means you’re in the clear, but this may not necessarily be true. First, while most new businesses have some sort of web presence, this is not universally the case. I still come across clients who have been operating for years with very little web presence. In that case, someone who is using a similar mark as theirs and relies only on an internet search may be misled into thinking their own mark is in the clear.

Also, search engines like Google don’t necessarily index all the information available on the web. Google strives to give you what it deems the most relevant results, and most times, it is pretty good at it, but this is also highly dependent on what search string you’re using. As with the federal search, don’t stop with a single search string, but play around with variations and tie in your field or specific goods/services. The more specific you get with this, the narrower your results will be which can be deceiving in terms of uncovering a conflict. Be careful not to start off too narrow – the idea behind both types of searches is that you want to follow multiple branches and narrow down as you go – don’t restrict yourself to a single search and call it a day. Other places you may want to look are publication advertisements, daily journals, domain registrations, and state entity formation records. Some of these records will have a cost associated for access while others may be free.

There are a variety of services that will provide a listing of both federal and common law searches and range in price based on the complexity and completeness, and will be higher in cost if an analysis is provided. You may want to get any results that you purchase analyzed by an attorney as they can be hundreds of pages and often mix in relevant results with outliers and it takes a trained eye who understands your business to pinpoint potential conflicts.

While I would highly recommend doing searches before beginning use of a trademark, and even more so before filing a trademark application, remember that it is almost impossible to uncover every mark that could be a potential issue (actually more of a cost benefit analysis – I’m sure if you had someone spend an inordinate amount of time doing limitless searches and uncovering all variations, you’d be golden, but this is going to be very cost prohibitive). I often have clients who are shaken by warnings about searches and elect to bypass them and instead hedge their bets whereby they request very basic federal searches, but pick multiple names that they like that are different enough and unlikely to get caught up with the same conflict. Once these trademarks get examined by the Trademark Office, they can pick the one they like the most that seems to have the fewest issues. This can be an effective strategy but someone can always come out of the woodworks and try to enforce senior common law rights against you even after your trademark has been granted registration. As such, beware. There is no foolproof search method or strategy in my opinion, but consider what you’re willing to spend in terms of time and money and do what best fits your risk tolerance.

B. Drafting Identification of Goods/Services

Every trademark application must have a precise and accurate description of goods/services letting the Trademark Office know what you (plan to) use your trademark for. While searches can be done with a general idea of what field/industry your usage is in, the more specific you can be, the more useful a search is. The Trademark Office has classified every good or service into forty-five “international classes” which may not be intuitive. Certain goods or services can fall into multiple classes depending on the material they’re made out of or the field of use for example. Classes 1 through 34 are all for goods and classes 35 through 45 are for services. These classifications are based on the Nice Classification, which was established by the Nice Agreement of 1957 and we’re currently (in 2016) on the tenth edition. There will be periodic changes to the classifications based on evolving standards of technology and usage so it is good to stay current on the most recent changes especially if your business is in the technology field.

As an international agreement, most countries try to make the classification system consistent by international class, but there are often many differences country by country in actual practice. As such, if you’re familiar with the classifications in another country, or have a foreign trademark registration, it may be slightly different in the U.S. at least as far as the specific entries within each classification is concerned.

The United States Trademark Office is very particular about the description of goods and services and may require more particularity within a certain classification than a foreign counterpart. As such, you may need to more definitively describe the goods and services compared to those on a foreign application.

My role with working with clients on drafting their description of goods and services is twofold. First, I want to ensure that the description is definite enough to satisfy the Trademark Office’s requirements of being precise. Second, I want to ensure that the description is broad enough to be accurate, without being overly specific to allow for potential growth.

For example, if a client tells me they sell lipstick and mascara, I could easily list “lipstick; mascara” which are in Class 003. However, if next year’s product lines will include eye liner and face powder, I have a bit of a dilemma. I can’t list “eye liner; face powder” along with “lipstick mascara” and claim all four are currently in use if they’re not. I would have to either file an application for the items currently in use and a separate application for those that are planned to be in use or not currently in use (or I could file different filing basis on a single application with the products currently in use distinguished as such and the products not yet in use distinguished as such, but the entire application will only be registered when all the products are in use. Thus the not-currently-in-use items may hold up the entire application until they’re in use).

In this situation, I may include the specific items separated by a semicolon to indicate different goods, but also try to find a broader description that still encompasses these goods allowing for growth without misstating my client’s offerings. For example, I know that “Cosmetics and make-up” is an acceptable identification as being definite enough to be accepted by the Trademark Office, which still gives my client room to grow within the market and not have to file multiple applications every year for each new product they release within this scope. This description would encompass the eye liner, face powder, lipstick and mascara, and would also cover other cosmetic items that may not yet be on the market under the trademark.

Keep in mind this does not mean that my client can stop someone else from using their trademark on a cosmetic item if the other party used it before they did, but does cast a broader net in terms of potential conflicts. I would argue that even if someone started using a similar trademark name on face powder before my client used their trademark on face powder, but that other party’s usage on face powder was after my client’s usage on lipstick, that lipstick and face powder are related enough as a cosmetic item that my client would still have superior rights based on prior usage of a related good.

If you’re unsure of how to classify your goods/services, you can use the Trademark Office’s Trademark ID Manual which sets forth common listings of goods and services by classification. Once your application is filed you can never broaden the scope beyond what you originally entered, but you can always narrow it down to be more specific, so it is important to properly (and not overly specifically) define your goods/services from the get-go so you have some wiggle room should the need arise to delete things that don’t apply or that raise conflicts.

C. Ownership

The easiest way to think about trademark ownership is that the party who uses a trademark in commerce is the owner of the rights associated with that mark. Rights are not created in a vacuum and must be (and continue to be) used in order to maintain ownership. Looking at ownership from this perspective shows us that rights are created not when the name is first thought of, but when use is actually made of the name or design in relation to specific goods or services.

My clients will often request that ownership of a trademark be filed under their names as individuals, or in the name of their company and it is important to understand the role this plays in the application process as well as continuing use of the trademark, especially in light of potential challenges down the road.

Chain of ownership from inception should be clearly documented. For example, if I start my own businesses offering legal services and I use a name to identify my services in such a manner that my customers can identify my services by such a name, I’ve created trademark rights in that name. Simple enough. However, one thing to keep in mind is whether I’ve formed an entity and whether I plan to do so in the future. Entrepreneurs have great ideas and some of the things my clients come up with astound me – the creative process they go through to market, brand and execute their ideas shows how passionate they are about their goals. However, entrepreneurs sometimes think a little differently in terms of linear progression. Sure they have this great idea, but if they haven’t incorporated yet, I can’t file a trademark application in the name of an entity that does not yet exist.

Think about forming an entity and speaking to tax professional about the legal and tax implications of operating an entity. Ensure that you have the proper agreements in place to cover the assignment of all the hard work you’ve done on behalf of the to-be-formed entity so that the entity will actually own the trademarks and other intellectual property you’ve created. If you have not yet formed an entity at this stage, you can file the trademark in the name of an individual and then assign the trademark rights through an assignment agreement to be filed with the Trademark Office once your entity is formed.

Be proactive about starting this process early and reduce the chain of title issues that may come up later on down the line. If a trademark is challenged at some point in the future, you must be able to show that it was used (and by who) from its inception, guaranteeing continuous use and transfer of rights in a manner which accounts for any change in ownership, even from an individual who created the company to the company itself once formed.

I encourage my clients to start thinking about ownership issues, especially in the context of starting a business with more than just one person. What happens if the business partners later on decide to split? Who gets the assets of the business? Write all this out and work with legal counsel to reduce these concerns to some type of agreement between all the owners of the business. When starting a business with others, you never want to think about what would happen if things fall apart, but I encourage my clients to address these issues before it comes to that.

While starting a business is exciting and it looks like there is only clear sailing from here on out, addressing and understanding potential wind down issues in the event of a disagreement is better to do before any such disagreements take place rather than leave expectations unstated which can lead to more problems.

Consider ownership in this context and discuss with your partners what happens to the business and its trademarks and other assets if one partner wants to leave or a disagreement takes place. Sometimes, this can take the form of a buyout by the remaining owners, or it may be more prudent to completely dissolve the business and divvy up any assets based on some agreement by the owners prior to any agreement. This way, ownership issues while the business is operating are clear and in the event of any issues, a clear plan is in place on what happens moving forward.

D. Filing Your Trademark Application

At this point, you’ve incorporated your business if you’re going down that route, have created some trademarks and perhaps have even begun to use them to offer goods and services to customers. You’ve had some research done as to potential conflicts and consulted with an attorney or spent some time looking into whether your mark is capable of functioning as a trademark and is sufficiently distinctive to qualify for trademark protection. Now, it’s time to file your trademark application.

If you’re doing this on your own, it is important to understand the components that make up a trademark application – most of which we’ve already gone over separately already. The first piece of information the Trademark Office will ask for is about the ownership of the trademark application, or the applicant information. The applicant information identifies the owner of the mark, not necessarily the individual who is filing the application. The owner may be an individual, corporation, partnership, or other type of legal entity.

The application must include the applicant’s name and address and additional information depending on who the owner is. If the owner is an individual, the citizenship of the owner(s) is required and if the owner is a corporation or limited liability company, the state or country of incorporation is required. If the owner is a partnership, limited partnership, joint venture, sole proprietorship, trust, estate or other type of entity, the type of entity (domestic entity or foreign equivalent) is required in addition to the state or country where legally organized, along with the name and citizenship of all general partners, active members, individuals, trustees, or executors for all domestic applicants. The applicant’s phone number, fax number, e-mail address and website may be provided, but are not required. If an attorney is filing the application on behalf of the applicant, you can designate this on the first step of the application, in which case you will be prompted to provide correspondence information for the attorney prior to submission of the application, or you can designate alternate contact information for the applicant as an individual/entity to act as the correspondent.

The next thing the Trademark Office will ask about is the actual mark you are seeking to register. Here you can request protection for a standard character mark or a special form (stylized/design) mark, and you can include any claim to color as shown in the design if you are protecting a logo mark.

Remember that your usage (current or planned) must be consistent with the drawing of the mark you are requesting protection for. Also at this step you’ll have the option to provide any additional statements in regards to the trademark application if appropriate. This information is intended to supplement the information required by the Trademark Office and you should not attempt to preemptively respond to any refusals here.

The idea is that you should provide any information that will help prosecution of your application be more expedient, such as disclaiming any descriptive or generic matter, citing any prior registrations for the same or similar marks that have already been granted, providing a translation or transliteration of any non-English wording or characters, providing the meaning or significance of any wording, letters or numerals in your mark, or providing any consent statements, among other such information.

Be careful about any additional statements you provide – sometimes it is better to allow full examination of the application by the examiner and then respond to any inquiries by the Trademark Office in due course. Applications may be filed for clients knowing full well that an Office Action will be received (an initial refusal requesting additional clarification) for something we could have entered when filing the application, but such information is left out to ensure that any information submitted is actually required. Additionally, leaving out such information ensures that the application is not needlessly limited preemptively.

After providing the ownership, mark information and any additional statements as relevant, you will then be able to provide the goods and services for which your trademark application will be used for. We’ve discussed the importance of properly drafting your identification of goods and services, and ensuring that the description is broad enough to encompass growth while being narrow and definite enough to be accepted by the Trademark Office.

Remember that the description must be precise and accurate – accuracy is key. If there are items within the description that are not relevant or not actually going to be provided, your application may be subject to third party challenge and so proper drafting and filing of this portion of your application is very important.

You can either use the Trademark Identification Manual (“ID Manual”), which is comprised of a listing of acceptable identifications of goods and services, or you can enter your goods/service in free form. The ID Manual contains identifications of goods and services and their classifications that are acceptable by the Trademark Office without further inquiry by an examining attorney (provided such identification and classification is supported by the specimens of record). The ID Manual is updated periodically, and the entries in it are more extensive and specific than the Alphabetical List under the Nice Classification.

Using identification language from the ID Manual enables trademark owners to avoid objections by examining attorneys concerning indefinite identifications of goods or services. However, applicants should note that they must assert actual use in commerce or a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce for the goods or services specified. Therefore, even if the identification is definite, examining attorneys may inquire as to whether the identification chosen accurately describes the applicant’s goods or services.

Along with the description of goods and services, you’ll have the option to indicate whether you are currently using the trademark in connection with those goods and services in commerce at the time of filing. If you’re not yet offering the goods or services in interstate commerce, you can indicate so but keep in mind that you will have to provide proof of your usage prior to registration once any other procedural or substantive issues are met (if any).

You’ll need to designate an address and contact information so that the Trademark Office can contact you if there are any issues, which we will discuss more below. The final step is to sign the application and submit the fees necessary for filing. Once you’ve done this, your application will be assigned a serial number which you can use to track to status of the trademark and you will receive a confirmation email or be able to download a pdf of your completed application for your records.

E. Prosecuting Your Trademark Application

Once your trademark application is filed and a serial number is assigned, the Trademark Office will make the record public in its database within a few days. Once made public, the Trademark Office will assign an examining attorney to review the application, which takes place about 3 to 4 months after the date of filing. Upon reviewing your application, the examining attorney may issue an Office Action if they require any additional information from you, and you will have six months to respond to any such refusal from the date of issuance. It is important to make sure your contact information is updated so that you are informed of any such action and are able to timely respond to any issues that are raised.

While we’re not going to go over every type of refusal in this text. Nonetheless, it is important to read and understand any Office Action that gets issued in order to submit a response that will satisfy the examiner to move your application forward to registration. The examiner will provide evidence supporting any refusal or request for additional information from the applicant and in responding to any such refusal, you can provide your own evidence as well.

If there are no issues raised, or you are successfully able to respond and alleviate any concerns the Trademark Office has, your application will then be published for a period of 30 days. This publication period allows third parties to object to your application should they feel that they have prior rights to your application, or raise any issues if they believe they may be damaged by the issuance of your trademark registration.

If there are no objections within this period, and you’ve already shown acceptable proof of use, your trademark application will then proceed to a final review and registration. If you have not yet shown proof of use, the Trademark Office will issue a Notice of Allowance, from which you will have 6 months to submit acceptable proof you are using your trademark in commerce, or file an extension for an additional 6 months of time to show proof of use. You can file up to five extensions before you need to show proof of use, but must do so timely before the period runs out.

Upon successful acceptance of your proof of use and any final review, your trademark application will proceed to registration.

Congratulations! You now have a federally registered trademark and all the benefits that come along with your registration. You will receive a registration certificate in the mail a few weeks after registration and can now start using the ® symbol after your mark.

F. Maintaining Your Trademark Registration

You’ve got your registration and your business is up and running, but you’ll still have to continuously file maintenance documents with the Trademark Office to show you are still using your trademark in commerce. The idea behind this is that only marks that are continuously in use are on the register and if a company stops using the trademark name, or fails to properly maintain their trademark registration, the federal rights will be extinguished, allowing someone else to come along and potentially use a similar trademark.

Your first renewal is due within the 5th and 6th year after the date of registration, and then subsequently every 9th and 10th year thereafter. You’ll need to show you are still using your trademark to keep your registration so it is important to keep records of usage in the ordinary course of business – this also helps in the event someone attempts to challenge your trademark rights.

By way of example (let’s use nice round numbers for this), if your trademark registration was granted on January 1, 2000, you can renew your trademark anytime between January 1, 2005 and January 1, 2006. Upon providing acceptable proof that you are still using your trademark, your renewal will be accepted and made of record by the Trademark Office. You’ll next need to show proof of use again and file a renewal between January 1, 2009 and January 1, 2010, and subsequently between every 9th and 10th here thereafter (January 1, 2019 to January 1, 2020, January 1, 2029 to January 1, 2030, etc.). As long as you continue to use your trademark, you can keep your trademark rights indefinitely. Failing to renew your trademark registration will result in cancellation of your federal rights and you may have to start the process over from the beginning in most situations. As such, make sure you remember to file these renewals in a timely manner to keep those hard earned rights in effect.

Enforcing Your Trademark

Now that you have your trademark registered and you’ve established your brand, you should use your trademark in a manner which informs other of your rights.

A. Proper Trademark Usage

I know we’ve talked about consistent usage throughout this text, and I’m going to mention it again here because yes, it is that important. While you’re free to use your trademark in a sentence, remember the idea behind trademark rights is to identify the source or origin of specific goods and services. You can of course use the ® symbol after your registered trademark and this lets competitors know that you’ve registered your brand. You should continue to use your trademark as a source identifier and actively police your trademark to ensure others are not infringing on your trademark rights, even inadvertently. This ensures that your customers associate your trademarks uniquely with you and not with an inferior product or service as offered by someone with a similar name.

B. Monitoring Third Party Usage

One of the main points of federal registration is that your trademark is presumed to be valid and so you should ensure that someone else does not use a similar name for competing goods or services. You should monitor third party usage through various means. A good customer service team and online presence where customers may actively reach out to you can be key. Customer service teams are the front lines of any business and can be a great source of information on issues that your business faces as it relates to its most key external aspects – customers. I tell my clients to monitor chats and ensure a system in place so they can take customer input up the chain to the proper decision makers when issues come up.

Often, clients will come to me about someone using a similar mark and when I ask how they found out about this other company they will tell me a customer mistakenly thought they were contacting that other company. Other times, people will leave reviews on their social media accounts or other online sources and it is clear that the customer is confused as to who they are actually trying to complain about – and a little digging shows they meant to review someone else’s product or service that is actually very similar (and inferior!) to their offering.

Thus start the process of ensuring you are properly monitoring other’s usage of similar marks and take action as necessary to stop such infringing usage if this negatively impacts your business. Even if such usage does not negatively impact your business and comes from a small competitor, you may want to actively monitor this usage and take action because you never know how that usage may grow in the future or become a problem later on.

Product and service expansions should be taken into account when looking at whether a mark you find is potentially infringing as certain goods and services are natural zones of expansion for your business and if someone is using a similar name as you for such a purpose you may have grounds to stop them based on your trademark rights.

While a good customer service team can warn of you such issues, you may also want to do some offensive monitoring. Set up alerts from your favorite search engine or news aggregator with key words that include your trademark name to monitor any common law usage that may infringe with your trademark. Periodically search the web for your trademark name and see what comes up and take note of how similar any other results are to your business and whether any brands or trademarks they are using may be confusing customers as to the source or origin of the products/services.

As far as federal database monitoring goes, you can periodically conduct searches with the Trademark Office for similar names so you can oppose any trademarks that you believe are confusingly similar to yours. While the Trademark Office does a pretty good job in issuing refusals for similar marks, an applicant may overcome such a refusal by deleting certain goods or services from their application so while the application may no longer be in conflict with your registration, their actual use may still be infringing.

There are many services out there that can periodically conduct both common law and federal database searches for a fee and report findings to you on a monthly or semi-monthly basis. You should review such reports with a legal professional as not all usage that gets found may be potentially similar.

C. Enforce Your Rights

If you do believe that someone else is using a trademark that is confusingly similar to your trademark, you should take action to prevent that usage from spreading. Allowing even a few small uses to go can result in your rights being diluted. Additionally, as more and more entrants start to see similar names being used, your rights may be diminished accordingly.

However, keep in mind that being overly aggressive can lead to a public relations disaster and there are many notable cases of companies trying to unfairly bully others to keep a competitive edge by enforcing weak marks or claiming potential infringement when goods and services are widely divergent or when names are not all that similar. Marketing is a PR game and bad PR can lose customers as fast as good PR can gain customers.

My advice to clients upon finding a potentially confusingly similar mark is to do some research into the company to find out who you’re dealing with. How long have they been in business? Who is running the business and what kind of resources do they have?

Many times, aggressive legal actions can be costly and counter-productive. Depending on the situation, I’ve advised clients to informally reach out to the company as any infringement may have been inadvertent and this sets a non-confrontational tone from the beginning. Instead of lawyering up right away (although you should definitely consult legal counsel), an informal conversation between business owners can not only lead to an amicable resolution between the parties, but I’ve seen where such a situation actually results in a burgeoning partnership where the two would-be competitors come to an agreement that mutually benefits each moving forward.

This can include an ongoing business relationship, sharing of resources, trading of domain names, etc. that would have never been on the table if an aggressive legal tactic was the first course of action.

Other times, the first step may be a send a cease and desist letter, but the format and tone of this letter is as important as the content. Think about how aggressive you want to be – there are times that an aggressive stance is warranted, but this is not always the case. A good cease and desist letter, depending on the situation, should serve to open dialog between the parties to resolve any potential infringement.

Should a cease and desist letter be ignored or if an unfavorable response is received and an open dialog or informal resolution does not seem possible, the next step may be to formally file suit either with the Trademark Office if the other party has a pending application or registered trademark, or in front of a state or federal court.

Keep in mind that litigation can be a costly and time consuming endeavor. Many times, a client will want to jump straight into this phase not realizing the intricacies and cost involved. If you go this route, prepare to hire legal counsel and dig in for the long haul depending on how aggressive you want to be and how aggressive or defensive the other party gets. Cases can go on for years and cost tens of thousands of dollars (if not more).

Once a case is instituted, clients will often tire of spending thousands of dollars a month. Often, after a couple months into the process, although the client may wish to stop, they’ve already spent a substantial amount of money. And unfortunately, in order to get any benefit out of the process, they will need to continue on all the way to the end for resolution. Be mindful of what your end goals are and work towards those goals – don’t throw good money after bad money.

References

| ↑1 | Britten Sessions and Mitesh Patel contributed to this article |

|---|