35 USC 102 Novelty

The present section is intended to give you some guidance on how to analyze section 102 rejections.

Strategies relating to 102 rejections are generally straight forward. In order for a 102 rejection to be valid, each and every part of the invention must be disclosed in one source. As such, in analyzing the rejection, the first thing to be done is to see if each and every claim element is actually found in the disclosed publication.

The M.P.E.P. provides some strategies you can use in your response:

‘[a] claim is anticipated only if each and every element as set forth in the claim is found, either expressly or inherently described, in a single prior art reference.’ Verdegaal Bros. v. Union Oil Co. of California, 814 F.2d 628, 631, 2 USPQ2d 1051, 1053 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

‘The identical invention must be shown in as complete detail as is contained in the … claim.’ Richardson v. Suzuki Motor Co., 868 F.2d 1226, 1236, 9 USPQ2d 1913, 1920 (Fed. Cir. 1989). [1]M.P.E.P. § 2131.

Additionally, “[e]very element of the claimed invention must be literally present, arranged as in the claim.” [2]Richardson v. Suzuki Motor Co., Ltd., 868 F.2d 1226, 1236 (Fed. Cir. 1989). Therefore, even if the prior art source has all of the elements of the claim, they must be arranged as is presented in the claim. This makes sense, however, for if our invention had the elements A, B, and C (e.g. think of a design of a chair, or the manner in which a computer program operates, or the manner in which a chemical molecule is combined together, etc.) and the prior art source discloses B, A, and C, in that order, it would make sense that such a prior art source would be potentially applicable (e.g. it has the same elements, etc.) but because the elements are not ordered in the same manner it does not disclose the claimed invention.

Lastly, 102 rejection are based on a single prior art source. Nonetheless, more than one source may arise with respect to inherency arguments. This comes up when a feature is an inherent characteristic of the thing taught in the primary reference. For example, prior art teaches A and B, but C would have been an inherent characteristic in combining A and B. Even though C was not taught in the prior art reference, because it is an inherent feature, other sources may be brought in. Consider this support:

To serve as an anticipation when the reference is silent about the asserted inherent characteristic, such gap in the reference may be filled with recourse to extrinsic evidence. Such evidence must make clear that the missing descriptive matter is necessarily present in the thing described in the reference. [3]Continental Can Co. v. Monsanto Co., 948 F.2d 1264, 1268 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

The use of extrinsic evidence is permissible to show that the missing descriptive material is necessarily present in the prior art reference description and that it would be so recognized by persons of ordinary skill. [4]Id. (citing In re Oelrich, 666 F.2d 578, 581 (CCPA 1981.))

In analyzing whether inherency arguments are proper, recognize, as indicated above, that support exists for the Examiner to rely on another reference to clarify a fact in the prior art source. However, the supporting reference must in fact do this. Therefore, determine whether the supporting reference actually discloses the fact that inherently is part of that disclosed in the prior art source.

As a quick overview, in order for a 102 rejection to be valid, ALL elements of the claims must be expressly taught by the single prior art reference. Remember that 102 is a test of novelty, and your invention must be novel. Therefore, when the Examiner puts forward a 102 rejection, in essence, the Examiner is indicating that all elements of your claim are being taught by the single prior art reference.

Usually, a 102 rejection can be expressly overcome by one of the following:

1. If the prior art reference does indeed teach all elements of the claims, then proceed forward with amending the claims to get around the prior art.

2. If the prior art reference does NOT teach all elements of the claims, then proceed forward with 1) putting forward arguments that rebut the rejection, and/or 2) putting forward additional amendments for the purposes of advancing prosecution.

Reference Material for 102 Rejections

During law school and when I studied for the patent bar, a lot of the class and study time was spent dissecting each part of section 102. Although we will analyze 102 here, recognize that much more (and many nuances) could be said further on the subject.

With the America Invents Act, some significant changes were brought about to section 102. As such, if you look online for arguments or strategies for section 102, make sure that you are looking at the updated requirements (implemented 03/2013). That being said, the new 102 does incorporate much of what was in the older 102, although numbering, formatting, and obviously some text is different as well.

The new changes to section 102 break the requirements into four parts: 1) novelty; 2) exceptions; 3) common ownership; and 4) prior art.

102(a)(1) & 102(b)(1): Conditions and Exceptions

(a) Novelty; Prior Art.— A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—

(1) the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention;

(b) Exceptions.—

(1) Disclosures made 1 year or less before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.— A disclosure made 1 year or less before the effective filing date of a claimed invention shall not be prior art to the claimed invention under subsection (a)(1) if—

(A) the disclosure was made by the inventor or joint inventor or by another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor; or

(B) the subject matter disclosed had, before such disclosure, been publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor or another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor.

It is helpful to remember that changes to section 102 were brought about to help it conform to more internationally recognized “first-to-file” patent systems. As such, the focus in the new section 102 is on defining prior art and exceptions to prior art. In short, if a prior art is found to which an exception does not apply, it may be applied to the invention disclosed.

First, 102(a) begins by indicating that a person shall be “entitled” to a patent. The burden therefore of showing that an invention does not meet the requirements is on the USPTO. Referencing our discussing above on Patent Examiners, their responsibility again is to determine whether the requirements are not met. If the requirements are met, then a person is entitled to a patent.

Next, 102(a)(1) mentions a “patented” or “printed publication” source. Such sources may include any preexisting publication anywhere in the world.

A “public use” is defined as that which is 1) accessible to the public and 2) commercially available. [5]“Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. Previously, section 102 included “secret” or “non public” sales. Now, however, section 102 does cover any secret or non public sale activity. Additionally, a secret or non public sale activity is one that assigns any obligation of confidentiality. [6]Id. This makes sense because if the material has not been made public, the inventor could not know of it.

As if to make its point, the statute then provides “or otherwise available,” which acts as a catch all for any other means of making the invention publicly available. The point here is simply to include any public material that is available in essentially any manner.

A “filing date” generally includes one of: 1) the filing date of the claimed invention; or 2) the filing date of an application the claimed invention depends on (e.g. claims priority to, etc.).

The exceptions which relate to 102(a)(1) are found in 102(b)(1) (as illustrated in Figure 18). Before analyzing the exceptions, three terms need to be briefly reviewed: disclosure, inventor, and one year or less. [7]See, e.g., id.

A disclosure “constitutes all documents and activities that were considered prior art.” [8]Id. Prior art includes any issued patent, published application, or any non-patent printed publication. Based on this understanding, a disclosure therefore is some evidence of the invention.

The term inventor is defined as “the individual who invented the device or, if it is a joint invention, the individuals who collectively invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” [9]Id. Additionally, the AIA has further indicated that “(g) The terms ‘joint inventor’ and ‘coinventor’ mean any one of the individuals who invented or discovered the subject matter of a joint invention.” [10]35 U.S.C. § 100(g).

Lastly, the term “one year or less” refers to a new AIA concept of grace period, which refers to the amount of time in which an inventor must file an application after a disclosure in order for the disclosure not to count as prior art. [11]“Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/.

With the above definitions in mind, let’s briefly review the two exceptions. First, 102(b)(1)(A) relates to providing an exception for “disclosures of the inventor’s own work (either by an inventor or a third party) that occur during the grace period.” [12]Id. As indicated by other attorneys, “[t]his [provision] simply continues the one year grace period practice established under the statutory bar provision of the Patent Act of 1952.” [13]Arpita Bhattacharyya et al, “The Not-So-Amazing Grace Period Under the AIA,” CIPA Journal (Sept. 2012), last accessed 04/24/2013), available at … Continue reading As such, this section relates to standard one year grace period associated with making a disclosure. In short, if a disclosure is made, an application must be filed by the inventor within a year in order for the disclosure not to be construed as prior art.

The next section, 102(b)(1)(B) relates to intervening disclosures. An intervening disclosure is simply a prior art disclosure before the filing date of the invention. This exception however permits the applicant to trace back to an earlier date if the inventor or inventor originated made a public disclosure before the intervening disclosure. Keep in mind that inventor or inventor originated public disclosure cannot be more than one year before the filing or the period would exceed the bounds of 102(b)(1) exception of a one year grace period. Although this exception can be quite useful in establishing priority, there are some potential warnings to be aware of. Consider the following:

the USPTO’s Proposed Rules for the “First-to-File” system, published in the July 26, 2012, issue of the Federal Register, has clarified that most disclosures by third parties will continue to be treated as prior art even when a third party disclosure is preceded by an inventor’s own public disclosure. According to the USPTO’s Proposed Rules, the § 102(b)(1)(B) exception can only be invoked if the subject matter in the third party disclosure is substantially identical to the subject matter previously disclosed by the inventor.

…

Consider the following scenario: Inventor Alpha invents a widget, but rather than keeping the invention a secret and promptly filing a patent application, Inventor Alpha publishes an article disclosing elements A and B of his widget invention. After reading Inventor Alpha’s article, Competitor Beta publishes his own article disclosing elements A, B, and C prior to the filing date of Inventor Alpha’s patent application. Since Competitor Beta’s article is not identical to Inventor Alpha’s prior disclosure, Competitor Beta’s article will become a prior art against Inventor Alpha’s patent application. That is, the one-year grace period cannot be invoked to remove Competitor Beta’s article as a prior art against Inventor Alpha’s patent application. [14]Id.

As such, although protection afforded by 102(b)(1)(B) does protect against intervening disclosure, recognize that it may be more narrowly construed than what the language initially conveys. Recognize additionally that this law is somewhat in flux as it was put into practice on March 16, 2013.

The question may have arisen as to how an inventor establishes the public disclosure to the USPTO. A Rule 130 declaration is used to show to the USPTO when a disclosure was made by the inventor. In fact, although each of the subsections relate to specific aspects of 120(b)(1) disclosures, in essence “the affidavit or declaration … must provide a satisfactory showing that the inventor or a joint inventor is in fact the inventor of the subject matter of the disclosure.” [15]Proposed Rule 130(b); Courtenay C. Brinckerhoff, “Comments: USPTO First-Inventor-To File Roundtable,” Sept. 6, 2012, available at … Continue reading

As far as guidelines, the Rule 130 Declaration should provide sufficient evidence that the disclosure was public (e.g. date, etc.), was made less than one year before the effective filing date of the invention, the content of the disclosure (e.g. is it the same as what was actually filed in the invention application, etc.), and who the disclosure was made by. [16]See, e.g., Courtenay C. Brinckerhoff, “Comments:

USPTO First-Inventor-To File Roundtable,” Sept. 6, 2012, available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/120906-fittf-roundtable.pdf. Note that if the authors of the disclosure are not the same as the listed inventors on the application that additional information may need to be supplied to show the discrepancy.

102(a)(1) & 102(b)(1): Examples

In the foregoing section, we analyzed the requirements for novelty and the exceptions. I find that the best way to really understand such information is through examples. The following examples and explanations are taken from USPTO provided powerpoint slides. [17]See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at … Continue reading

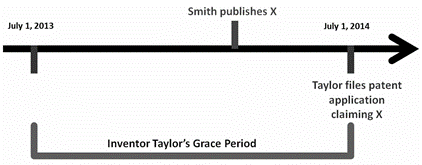

Example 1: Exception in 102(b)(1)(A)

Taylor’s publication is not available as prior art against Taylor’s application because of the exception under 102(b)(1)(A) for a grace period disclosure by an inventor.

Example 2: Exception in 102(b)(1)(A)

Smith’s publication would be prior art to Taylor under 102(a)(1) if it does not fall within any exception in 102(b)(1). However, if Smith obtained subject matter X from Taylor, then it falls into the 102(b)(1)(A) exception as a grace period disclosure obtained from the inventor, and is not prior art to Taylor.

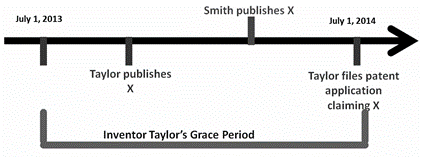

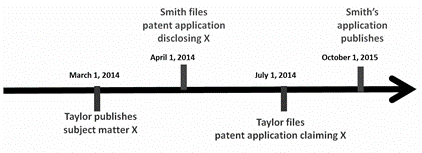

Example 3: Exception in 102(b)(1)(B)

Smith’s publication is not prior art because of the exception under 102(b)(1)(B) for a grace period intervening disclosure by a third party. Taylor’s publication is not prior art because of the exception under 102(b)(1)(A) for a grace period disclosure by the inventor. If Taylor’s disclosure had been before the grace period, it would be prior art against his own application. However, it would still render Smith inapplicable as prior art.

102(a)(2) & 102(b)(2): Conditions and Exceptions

(a) Novelty; Prior Art.— A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—

…

(2) the claimed invention was described in a patent issued under section 151, or in an application for patent published or deemed published under section 122 (b), in which the patent or application, as the case may be, names another inventor and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.

(b) Exceptions.—

…

(2) Disclosures appearing in applications and patents.— A disclosure shall not be prior art to a claimed invention under subsection (a)(2) if—

(A) the subject matter disclosed was obtained directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor;

(B) the subject matter disclosed had, before such subject matter was effectively filed under subsection (a)(2), been publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor or another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor; or

(C) the subject matter disclosed and the claimed invention, not later than the effective filing date of the claimed invention, were owned by the same person or subject to an obligation of assignment to the same person.

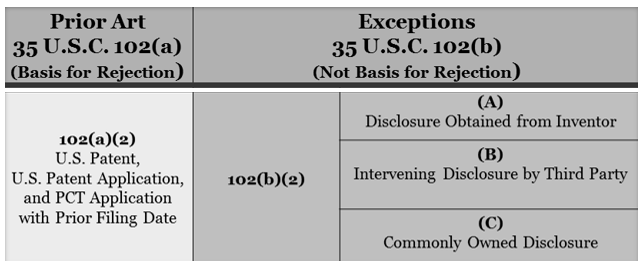

AIA Statutory Framework [18]“Public Forum: First-Inventor-File Final Rules and Guidance,” USPTO Public Forum Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/.

Section 102(a)(2) continues a theme that we discussed above with respect to 102(a)(1) in that it discusses further examples of prior art. In particular, the statute references “section 151” and “section 122 (b).”

Section 151 of Title 35 refers simply to issued and published US patents. [19]See, e.g., 35 U.S.C. § 151. Section 122(b) relates to a published US patent application, or a published patent application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) that designates the United States. [20]See, e.g., 35 U.S.C. § 121(b); “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at … Continue reading In short, 122(b) refers to either a published application filed directly with the USTPO or through the PCT.

There are three exceptions that apply to these relatively straight forward rules. Before reviewing the exceptions, it is important to clarify two terms: PCT and effective filing date. [21]See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at … Continue reading

We have previously discussed foreign filing considerations. A PCT application permits the applicant to obtain international patent protection by establishing an international effective filing date for their invention. [22]See, e.g., id. After a set time period, the application may enter the national stage in any country that was designated in the PCT application. If filing within the United States, the application must enter national phase by 30 months. [23]See, e.g., “Time Limits for Entering National/Regional Phase under PCT Chapters I and II,” WIP PCT (Sept. 7, 2012), last accessed 04/24/2013, available at … Continue reading Additionally, although it may be obvious, an individual application must be filed in each country where protection is sought. To more fully get an overview of the process of a PCT application, a flowchart has been reproduced later in the next chapter (dealing with PCT foreign filing practices).

Additionally, a filing date is simply the date on which an application is filed. The effective filing date is a bit broader than simply a filing date, as it may include filing dates of a claim to priority. For example, an application may be filed 01/01/10 but may claim priority to a provisional, or to another application (e.g. think of a continuation, etc.) which may cause the effective filing date to be earlier, such as 01/01/09. With respect to a prior art source, the document must have an effective filing date before the effective filing date of the patent application under examination.

Further, in determining whether something is applicable as prior art (e.g. which relates to the effective filing date, etc.) under this section, 102(d) provides the following:

(d) Patents and Published Applications Effective as Prior Art.— For purposes of determining whether a patent or application for patent is prior art to a claimed invention under subsection (a)(2), such patent or application shall be considered to have been effectively filed, with respect to any subject matter described in the patent or application—

(1) if paragraph (2) does not apply, as of the actual filing date of the patent or the application for patent; or

(2) if the patent or application for patent is entitled to claim a right of priority under section 119, 365 (a), or 365 (b), or to claim the benefit of an earlier filing date under section 120, 121, or 365 (c), based upon 1 or more prior filed applications for patent, as of the filing date of the earliest such application that describes the subject matter.

In discussing the applicable exceptions in this section, keep in mind that such exceptions only apply to potential prior art, including US Patents, US Patent applications which have been published, or PCT published applications, whose effective filing date predates the claimed invention’s effective filing date.

Section 102(b)(2)(A) is where a disclosure made by someone who acquired the claimed invention’s subject matter from its inventor(s) will not be considered prior art for the claimed invention. [24]“Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/.

Section 102(b)(2)(B) relates to disclosures made by the inventor(s) prior to the subject matter’s disclosure in documents. [25]Id. Additionally, there is no requirement that this type of disclosure be the same as (or verbatim) to a disclosure of a US patent, a US published application, or a published PCT application. [26]Id.

Lastly, section 102(b)(2)(C) relates to prior art which was filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention, but which would not be considered prior art if the claimed invention and the disclosed subject matter are owned by (or under obligation to assign to) the same person. [27]Id.

Again, recognize that all 102(b)(2) exceptions relate only to 102(a)(2) prior source documents, which may act as prior art from the date they are effective filed. [28]“Public Forum: First-Inventor-File Final Rules and Guidance,” USPTO Public Forum Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. As such, a grace period is not relevant to 102(b)(2) prior art sources.

In addition to these exceptions, 102(c) relates to 102(b)(2)(C):

(c) Common Ownership Under Joint Research Agreements.— Subject matter disclosed and a claimed invention shall be deemed to have been owned by the same person or subject to an obligation of assignment to the same person in applying the provisions of subsection (b)(2)(C) if—

(1) the subject matter disclosed was developed and the claimed invention was made by, or on behalf of, 1 or more parties to a joint research agreement that was in effect on or before the effective filing date of the claimed invention;

(2) the claimed invention was made as a result of activities undertaken within the scope of the joint research agreement; and

(3) the application for patent for the claimed invention discloses or is amended to disclose the names of the parties to the joint research agreement.

Section 102(c) focuses on common ownership under a joint research agreement. Additionally, 102(c) embodies the 2004 Cooperative Research and Technology Enhancement (“CREATE”) Act:

The enactment of section 102 (c) of title 35, United States Code, under paragraph (1) of this subsection is done with the same intent to promote joint research activities that was expressed, including in the legislative history, through the enactment of the Cooperative Research and Technology Enhancement Act of 2004. [29]See, e.g., “Notes” to 35 U.S.C. § 102.

Under current law, common ownership or that which is subject to a joint research agreement has some implication to section 103(c) which, as we will discuss below, excludes prior art for obviousness purposes. However, section 102(c) expands the 103(c) exclusion to also exclude such prior art disclosures within a year of the application’s filing date for novelty purposes as well. [30]See, e.g., “America Invents Act: New Section 102,” Inventive Step Blog (Oct. 12, 2011), last accessed 04/24/2013, available at … Continue reading

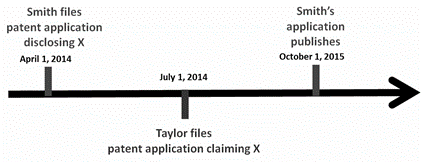

102(a)(2) & 102(b)(2): Examples

The following examples should aid you in understanding the exceptions to 102(b)(2). As indicated above, the following examples and explanations are taken from USPTO provided powerpoint slides. [31]See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at … Continue reading

Example 1: Exception in 102(b)(2)(A)

Smith’s patent application publication is not prior art if Smith obtained X from Inventor Taylor because of the exception under 102(b)(2)(A) for a disclosure obtained from the inventor

Example 2: Exception in 102(b)(2)(B)

Smith’s patent application publication is not prior art against Taylor’s application because of the exception under 102(b)(2)(B) for an intervening disclosure by a third party.

Example 3: Exception in 102(b)(2)(C)

Smith’s patent application publication is not prior art because of the exception under 102(b)(2)(C) for a commonly owned disclosure. There is no requirement that Smith’s and Taylor’s subject matter be the same in order for the common ownership exception to apply.

Pre-AIA v. Post-AIA Considerations

Most likely, those that are studying this book will deal most frequently with post-AIA procedures and rules described above. Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that you will most likely need to apply both Pre-AIA and Post-AIA rules. For the Patent Bar Exam, you will need to know how to identify which set of rules to apply and apply them flawlessly and quickly.

Although many of the above considerations are specific to post-AIA, the pre-AIA 102 rules were a bit more complex. The greatest difference was that pre-AIA focused on a “first-to-invent” system whereas the post-AIA focused on a “first-to-file” which simplified the 102 rules a bit. If you receive an office action response dealing with Pre-AIA rules, I would recommend looking up the specific old Rule 102 section. Additionally, a plethora of sites online provide best strategies for dealing with each of the pre-AIA 102 rules.

Under pre-AIA rules, the focus was on who was the first to invent. Therefore, an applicant could “swear back” to a prior time of when the invention was actually invented. This “swearing back” process included providing some form of evidence to show the invention had been substantially created at a specific time. Additionally, the inventor was required to exercise “diligence” from the date the invention was conceived (called a date of conception) up until the time that the invention was actually reduced to practice. A quick example:

01/01/2010: Inventor A conceives invention

02/01/2010: Inventor B conceives invention

03/01/2010: Inventor B reduces to practice

04/01/2010: Inventor A reduces to practice

05/01/2010: Inventor B files a patent application

06/01/2010: Inventor A files a patent application

Who gets the resulting patent? Inventor A would be eligible for patent protection (e.g. by swearing back to 01/01/2010, etc.) if the inventor can prove that he/she was diligent from the initial time of the invention being conceived to actually reducing to practice the invention.

Based on this example, the pre-AIA rules focused heavily on ensuring that the actual inventor received the final patent. This is an important point, particularly because if an invention is filed now, we simply look at effective dates rather than having to delve into who actually invented the invention first. The scope of prior art therefore is broadened as a result of the AIA rules (e.g. inventor can no longer swear behind a reference, etc.). This is one of the reasons why a great rush of filing applications occurred just prior to the March 16, 2013 implementation of the AIA rules.

In comparing the two systems (Pre and Post AIA), some potential issues arise that you should be aware of. In the most simple of examples, if an application was filed on or after 3/16/13, then it would be under post-AIA rules. If the application was filed on or before 3/15/13, it would be under pre-AIA rules. However, if we start with priority documents, then this gets a little tricky. For example, let’s say we file a provisional on 3/15/13. We later file an application claiming priority to the provisional on 3/16/13. The application however contains the same information as disclosed in the priority document. Based off of such, the application will be prosecuted under pre-AIA rules. Let’s take the same example but now the specification is not the same between the application as filed and the priority document. In this instance, AIA may apply. If the claimed subject matter was fully supported in the priority document, then the application will be prosecuted under pre-AIA. If, however, the claimed subject was not disclosed in the priority document, then the application will be prosecuted under post-AIA rules.

Additionally, let’s say you are prosecuting a patent under pre-AIA rules. An amendment to the claims is entered (consistent with the Specification), but unbeknownst to you, such support was not found in the priority document. This would automatically trigger the prosecution to switch from pre-AIA to post-AIA rules. Even if you go back and delete the entered in material (e.g. to conform it with priority document), it does not matter. Once an application has been switched to post-AIA, it cannot go back to pre-AIA.

The reality is that the post-AIA rules that we have reviewed in this book will become ultimately the focus of the US patent system. Nonetheless, the States are in a period of transition from one system to another. As such, be aware of these considerations.

Recognize also that for any application that you file now will be based on post-AIA rules. Nonetheless, as a patent practitioner you may be asked to work on applications that are still under pre-AIA rules. Make sure therefore that you navigate the transition waters correctly.

Additional 102 Arguments

Inherency

102 novelty requires that each limitation be shown in a single reference. If not all limitations are shown, the Examiner may rely on an inherency argument that such feature is “inherently” part of the prior art. In response, you can provide arguments on how not every feature of the claimed invention is being met by the prior art reference.

No Reasoning

The Examiner has the burden of putting forth, in complete detail, how each and every claim element is shown by the cited art. Often, the Examiner may apply globally the entire reference to the claim or the limitations without specifically pointing out in detail how each feature is being met by the prior art.

Not Prior Art

The prior art must qualify as prior art to be valid. A good habit to get into is to double check to verify if the prior art is indeed prior art. It sounds almost too banal for this to even be mentioned. That being said, I’ve seen instances where the prior art supplied was filed after the priority date of the application, in which case, the prior art is in fact not prior art and cannot be relied upon by the Examiner. Other potential topics that may arise include:

- Whether the prior art is a publication of applicant’s own invention. Remember that there are some potential exceptions which might apply if the prior art originates from the same inventor.

- Whether the prior art is not publicly available. If it was not publicly available, it may not qualify as prior art.

Misconstruction of a Claim Element

Misunderstandings, like many other parts of life, arise also in the prosecution context. The Examiner simply may not have correctly interpreted the claim language. If such is the case, a phone call (or Examiner’s Interview) may assist in their understanding. Sometimes, the claim language may be amended to more clearly show how the claim or limitation is to be interpreted.

Misconstruction of the Asserted Reference

Misunderstanding may also apply to the prior art reference. The Examiner may feel a certain art reference teaches a particular subject matter. In all reality, however, it may not. You can right the wrong by, again, bringing it to the Examiner’s attention. That being said, be tactful in stating that the prior art was incorrectly interpreted. Such could be construed as a type of “slap in the face” to the Examiner – and you want to avoid causing offense. I’d also note that these types of issues often are the basis for appeals – where the Examiner maintains a prior art reference does teach X, and the applicant asserts it does not teach X.

References

| ↑1 | M.P.E.P. § 2131. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Richardson v. Suzuki Motor Co., Ltd., 868 F.2d 1226, 1236 (Fed. Cir. 1989). |

| ↑3 | Continental Can Co. v. Monsanto Co., 948 F.2d 1264, 1268 (Fed. Cir. 1991). |

| ↑4 | Id. (citing In re Oelrich, 666 F.2d 578, 581 (CCPA 1981 |

| ↑5 | “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑6 | Id. |

| ↑7 | See, e.g., id. |

| ↑8 | Id. |

| ↑9 | Id. |

| ↑10 | 35 U.S.C. § 100(g). |

| ↑11 | “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑12 | Id. |

| ↑13 | Arpita Bhattacharyya et al, “The Not-So-Amazing Grace Period Under the AIA,” CIPA Journal (Sept. 2012), last accessed 04/24/2013), available at http://www.finnegan.com/resources/articles/articlesdetail.aspx?news=4acad2aa-4430-4d87-a197-3a202ac17c5b. |

| ↑14 | Id. |

| ↑15 | Proposed Rule 130(b); Courtenay C. Brinckerhoff, “Comments:

USPTO First-Inventor-To File Roundtable,” Sept. 6, 2012, available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/120906-fittf-roundtable.pdf. |

| ↑16 | See, e.g., Courtenay C. Brinckerhoff, “Comments:

USPTO First-Inventor-To File Roundtable,” Sept. 6, 2012, available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/120906-fittf-roundtable.pdf. |

| ↑17 | See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑18 | “Public Forum: First-Inventor-File Final Rules and Guidance,” USPTO Public Forum Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑19 | See, e.g., 35 U.S.C. § 151. |

| ↑20 | See, e.g., 35 U.S.C. § 121(b); “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑21 | See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑22 | See, e.g., id. |

| ↑23 | See, e.g., “Time Limits for Entering National/Regional Phase under PCT Chapters I and II,” WIP PCT (Sept. 7, 2012), last accessed 04/24/2013, available at http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/texts/time_limits.html. |

| ↑24 | “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(2)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(2),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑25 | Id. |

| ↑26 | Id. |

| ↑27 | Id. |

| ↑28 | “Public Forum: First-Inventor-File Final Rules and Guidance,” USPTO Public Forum Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |

| ↑29 | See, e.g., “Notes” to 35 U.S.C. § 102. |

| ↑30 | See, e.g., “America Invents Act: New Section 102,” Inventive Step Blog (Oct. 12, 2011), last accessed 04/24/2013, available at http://inventivestep.net/2011/10/12/america-invents-act-new-section-102/. |

| ↑31 | See, e.g., “Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1)” and “Exceptions to Prior Art Under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1),” USPTO Slides (Mar. 15, 2013), available at http://www.uspto.gov/aia_implementation/. |