Goliath v. Goliath Fallout: Repercussions of Apple v. Samsung[1]Britten Sessions and Wei Y. Lu contributed to this article

Patent litigation is typically the ideal battleground of emotional sway. The lone inventor, working tirelessly in his garage, uncovers and creates a new technology that will change the world forever. In the midst of his hard work, a large corporation craftily enters the picture, steals the beloved invention, and proceeds to reap millions off of the honest inventor’s hard work. Now enter the patent litigators, crusaders for the lone inventor, seeking to right the obvious wrongs. From one perspective, patent litigation helps the public feel that justice has been served. The lowly small inventor, a David of a plaintiff, succeeds in taking down a Goliath of an adversary.

But what if the plaintiff is also a Goliath?

This is the exact situation in the landmark case Apple v. Samsung. [2]See, e.g., Ashby Jones and Jessica E. Vascellaro, Apple v. Samsung: The Patent Trial of the Century, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, (July 24, 2012), available at … Continue reading Both companies are giants in the high technology industry, creating devices and products that are essentially ubiquitous. [3]See, e.g., Juro Osawa and Sven Grundberg, Apple’s Smartphone Market Share Drops as Samsung’s Edges Up, DIGITS, (January 28, 2014,7:28 a.m.) … Continue reading) Each makes billions of dollars in profits [4]See, e.g., Ryan Knutson, Samsung Dethrones Apple in Smartphone Profits, DIGITS, (July 26, 2013, 3:44 p.m.) http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2013/07/26/samsung-dethrones-apple-in-smartphone-profits/ … Continue reading . And each is out to take down the other. [5]See, e.g., Julianne Pepitone, Apple vs. Samsung scorecard, (August 8, 2013, 9:27 A.M. Eastern) http://money.cnn.com/2013/08/08/technology/mobile/apple-samsung-timeline/ (“The … Continue reading

This article will first analyze in Part I the procedural aspects of the Apple v. Samsung case, including reviewing all matters that relate to this central dispute. Secondly, Part II of this article will investigate the possible repercussions of the Apple v. Samsung case.

Part I: Case Analysis of Apple v. Samsung

Starting in 2011, Apple Inc. (“Apple”) challenged Samsung Electronics (“Samsung”) to a series of legal battles that spanned ten countries and four continents. [6]See Florian Mueller, List of 50+ Apple-Samsung Lawsuits in 10 Countries, Foss Patents (April 28, 2012), http://www.fosspatents.com/2012/04/list-of-50-apple-samsung-lawsuits-in-10.html; see also, … Continue reading Within the United States alone, these clashes occurred in three main jurisdictions: the Federal Courts, [7]See, e.g., Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 7036077 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 2, 2011); Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co.; Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. … Continue reading the International Trade Commission (“ITC”), [8]See, e.g., ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, Jun. 28, 2011; ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, July 5, 2011. and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). [9]See Florian Mueller, Apple’s Two Most Important Multitouch Software Patents Face Anonymous Challenges at the USPTO, Foss Patents (May 29, 2012), … Continue reading

1. United States Federal Courts

The first battle of the series began with a lawsuit in the federal court. [10]See generally, Plaintiff’s Complaint, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. CV-11-01846, 2011 WL 1523876 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 15, 2011). This litigation was the Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co. case (“Apple v. Samsung I”) filed on April 15, 2011. [11]See id. Interestingly, even before the first conflict had been resolved, a second lawsuit was filed on February 8, 2012 (“Apple v. Samsung II”), with a trial set for March 2014. [12]Case Management Order, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 12-CV-00630-LHK, at pp. 2 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2013).

Apple v. Samsung I

The first of the disputes began with Apple filing suit against Samsung in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, asserting patent infringement claims on ten patents and a trade dress infringement claim. [13]Plaintiff’s Complaint, Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. CV-11-01846, 2011 WL 1523876, at paragraph 24-26 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 15, 2011). In a subsequent amended complaint, Apple included five additional patents to its lawsuit. [14]Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 2582932, at paragraph 28-29 (N.D. Cal. June 16, 2011). Of the fifteen asserted patents, eight were utility patents and seven were design patents. [15]Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 2582932, at paragraph 28-29 (N.D. Cal. June 16, 2011). Apple accused Samsung of infringement on its … Continue reading and on its design patents (U.S. Patent Nos. D627,790 (“D’790”), D617,334 (“D’334”), D604,305 (“D’305”), D593,087 (“D’087”), D618,677 (“D’677”), D622,270 (“D’270”), and D504,889 (“D’889”)). Id. at paragraph 28.))

Naturally, Samsung denied all allegations of infringement. [16]Samsung Entities’ Answer, Affirmative Defenses, and Counterclaims to Apple Inc.’s Amended Complaint, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-cv-01846-LHK, at paragraph 1 (N.D. Cal. June 30, … Continue reading Included in its answer, Samsung countersued Apple with its claims of patent infringement, asserting twelve of Samsung’s patents. [17]Id. Notably, although the focus of this article will be on patent related matters, other intellectual property matters were also included in this dispute. [18]See, e.g., Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 2582932.; see also, David Pierce, Jury: Samsung diluted Apple’s trade dress for … Continue reading

Preliminary Injunction

Two and a half months after Apple filed its complaint on July 1, 2011, Apple motioned for its first preliminary injunction on Samsung’s products for infringing Apple’s asserted patents. [19]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 7036077, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 2, 2011). In its motion, Apple requested the court to enjoin Samsung from making, using, offering to sell, and import into the United States the Galaxy S 4G, Infuse 4G, and Galaxy Tab 10.1 because these products infringed upon the D’677 patent, the D’087 patent, the D’889 patent, and the ‘381 patent. [20]Id. Additionally, Apple included Samsung’s Droid Charge in the motion for preliminary injunction because of its infringement upon the ‘381 patent. [21]Id.

Unfortunately for Apple, the court denied the motion in an order on December 2, 2011. [22]Id. Judge Lucy H. Koh, the presiding judge over the Apple v. Samsung I case, ruled that Apple had failed to establish all four factors required for a preliminary injunction [23]The four factors used by the district court in determining whether a motion for preliminary injunction can be granted are: “(1) some likelihood of success on the merits of the underlying … Continue reading; see also, Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008).)) for the four asserted patents. [24]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 7036077, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 2, 2011). More specifically, because Judge Koh found that there were validity issues with two of the patents (D’087 and D’889), and because Apple did not show how an injunction on Samsung’s accused products would prevent irreparable harm to Apple, Judge Koh denied Apple’s motion for preliminary injunction. [25]Id.

Consequently, Apple appealed the denial to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit”). [26]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1316 (Fed. Cir. 2012). In its decision on May 14, 2012, the Federal Circuit affirmed the denial of preliminary injunctive relief for three of the four patents (D’087, D’667, and ‘381) at issue. [27]Id. As for the fourth patent (D’889), the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court had committed legal error by not analyzing the balance of hardships and the public interest factors. [28]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1332-33 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Additionally, the court reasoned that even though the district court had found substantial question as to the validity of the D’889 patent, the district court must weigh the balance of hardships and public interest factors in its analysis of preliminary injunction. [29]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Because the district court had not made any findings with respect to the last two factors, the Federal Circuit vacated that portion of the court order and remanded the matter to the district court for further proceedings. [30]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1332-33 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Pursuant to Federal Circuit’s order, the district court reevaluated the preliminary injunction for the D’889 patent and made findings as to the balance of hardships and public interest factors. [31]See generally Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2012 WL 2401680 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 26, 2012). In the June 26, 2012 order, Judge Koh took note of Federal Circuit’s reversal of the district court’s finding of invalidity of the D’889 patent in her analysis. [32]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2012 WL 2401680, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 26, 2012). Because of the reversal, Judge Koh found the balance of hardships to tip in favor of Apple. [33]Id. Further, the public interest factor was also found in favor of Apple. [34]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2012 WL 2401680, at *3-4 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 26, 2012). With the first two factors — likelihood of success on the merits and irreparable harm — successfully established by Apple in the previous order, coupled with the Federal Circuit’s finding that Samsung is not likely to establish invalidity of D’889 at trial, the district court granted preliminary injunction to Apple on the D’889 patent. Because the D’889 patent affected only the Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1, [35]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2011 WL 7036077, at *24 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 2, 2011), (In Apple’s motion for preliminary injunction, Apple sought to enjoin the sale of the … Continue reading the district court enjoined the domestic sale of the Galaxy Tab 10.1. [36]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2012 WL 2401680, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 26, 2012). Apple posted the required $2.6 million bond for the injunction. [37]Florian Mueller, Apple Posts Bond and Wins Battle Over Expert Reports, Samsung Moves to Stay Injunction, Foss Patents, (June 28, 2012), … Continue reading

Samsung immediately appealed the injunction. [38]Id. Even though Samsung requested a stay on the injunction to the district court while the injunction was being appealed to the Federal Circuit, [39]Florian Mueller, Federal Circuit Denies Immediate Stay of Galaxy Tab 10.1 Injunction, No Nexus Decision Yet, Foss Patents, (July 6, 2012), … Continue reading the district court denied the motion. [40]Order Denying Samsung’s Motion to Stay, Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, at pp. 13 (July 2, 2012). Additionally, the Federal Circuit also denied Samsung’s motion for a stay. [41]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 2012-1506, at *5 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Jury Trial

On July 30, 2012, the highly anticipated jury trial between Apple and Samsung began. Internal emails, design plans, and technical discussions on the smartphone were argued by attorneys of both sides. [42]Jessica E. Vascellaro, Apple and Samsung Trade Jabs in Court, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, July 31, 2012, available at, … Continue reading Apple primarily argued that Samsung copied the iPhone design, while Samsung argued that Apple should not be granted a monopoly essentially for a rectangular shape. [43]Id.

After about four weeks of trial, the jury returned with a verdict on August 24, 2012. [44]Joe Mullin, Apple v. Samsung verdict is in: $1 billion loss for Samsung, ARS TECHNICA, (August 24, 2012, 2:57 PDT) http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2012/08/jury-returns-verdict-in-apple-v-samsung/. The verdict found in favor of Apple, awarding Apple $1.051 billion in damages. [45]Id. The jury ruled that Samsung had willfully infringed on Apple’s design and utility patents and had also diluted Apple’s trade dresses related to the iPhone. [46]Mikey Campbell, Samsung guilty of patent infringement, Apple awarded nearly $1.05B, (August 24, 2012,2:47 p.m. PT) … Continue reading Of the fifteen originally asserted patents, the jury only found five Apple patents to have been infringed: the ‘381 patent (rubber-banding), the ‘915 patent (pinch-to-zoom API), the ‘163 patent (tap-to-zoom-and-navigate), the D’087 patent, and the D’305 patent. [47]Id.

Most notably, the jury returned with the verdict that the Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 did not infringe upon Apple’s D’889 patent. [48]Id. Because of this verdict, the district court lifted the preliminary injunction on the Galaxy Tab 10.1. [49]Pamela Jones, Judge Koh Dissolves Preliminary Injunction on Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1; Apple May Owe Samsung, Groklaw, (October 2, 2012, 12:18 a.m ET) … Continue reading Samsung requested a hold on the payment of the $2.6 million bond Apple had posted for the preliminary injunction, pending the post-trial motions in December 2012. [50]Id.

Permanent Injunction

Making use of its victory against Samsung, Apple immediately filed a request for a permanent injunction against Samsung’s products. [51]See generally Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 909 F. Supp. 2d 1147 (N.D. Cal. 2012). Unfortunately for Apple, this request was subsequently denied in a district court order on December 17, 2012. [52]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 909 F. Supp. 2d 1147, 1149-50 (N.D. Cal. 2012).

Accordingly, Apple appealed the denial of permanent injunction to the Federal Circuit. [53]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 735 F.3d 1352, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2013). On November 18, 2013, the Federal Circuit issued an order affirming in Judge Koh’s denial of the injunction, vacating in part and remanding for further proceedings. [54]Id.

With respect to the permanent injunction relating to the design patents (D’305, D’087, and D’677), the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial, finding that the district court did not abuse its discretion by ruling that Apple had failed to show a causal nexus between Samsung’s infringement and Apple’s lost market share and sales. [55]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 735 F.3d 1352, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2013). The Federal Circuit also affirmed the denial of the injunction relating to the trade dress claim on the grounds that Samsung had stopped selling and had not shown any evidence of resuming to sell the products that were diluting Apple’s trade dress. [56]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 735 F.3d 1352, 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

On the other hand, the Federal Circuit vacated the denial of the injunction relating to utility patents (‘381, ‘915, and ‘163) and remanded the matter back to the district court for further proceedings. [57]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 735 F.3d 1352, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2013). The Federal Circuit found that the district court abused its discretion in its analysis of the irreparable harm and the inadequacy of legal remedies factors for the utility patents. [58]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 735 F.3d 1352, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2013). The court used the eBay factors in determining whether permanent injunction should be granted. Id. at 1359. The eBay factors … Continue reading This decision provided Apple another chance for a permanent patent injunction against Samsung’s smartphones relating to the three multitouch software patents: the ‘381 patent (rubber-banding), the ‘915 patent (pinch-to-zoom API), and the ‘163 patent (tap-to-zoom-and-navigate). [59]Florian Mueller, Appeals Court Revives Apple’s Bid for Permanent U.S. Sales Ban Against Samsung’s Android Devices, Foss Patents, (November 18, 2013), … Continue reading

As a consequence, Apple filed a renewed motion for a permanent injunction on the utility patents on December 26, 2013, the same day the Federal Circuit issued the formal mandate to the district court. [60]Apple Inc.’s Renewed Motion for a Permanent Injunction, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-cv-01846-LHK (PSG), at pp. i (Dec. 26, 2013). Within its motion, Apple requested an injunction hearing for January 30, 2014. [61]Id.

Damages Retrial

Because of certain errors during the jury trial, Judge Koh vacated $450 million of the original award and ordered a new jury to recalculate damages. [62]Philip Elmer-DeWitt, Apple’s $1B award from Samsung reduced to $600M, CNNMONEY, (March 1, 2013, 4:05 p.m ET) http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2013/03/01/apple-samsung-600-million/ (“In a 27-page … Continue reading

On numerous occasions, prior to and during the retrial, Samsung asked the district court to stay the proceeding because of the pending reexaminations affecting Apple’s ‘949 patent (touchscreen heuristics), the ‘915 patent (pinch-to-zoom API), and the ‘381 patents (rubber-banding), which were all at issue in the retrial. [63]John Ribeiro, Judge refuses to stay Apple-Samsung lawsuit pending patent review, GOOD GEAR GUIDE, (November 26, 2013, 7:00 p.m). … Continue reading Not wanting to delay the case any further, Judge Koh denied the requests for a stay and proceeded with the retrial on schedule. [64]Id.

The retrial for damages concluded in November 2013. [65]Michael Phillips, Apple Vs. Samsung: A Patent War With Few Winners, THE NEW YORKER, (November 22, 2013), … Continue reading The new jury awarded $290 million to Apple for Samsung’s infringement on Apple’s patents. [66]Darrell Etherington, Apple Awarded $290M By Jury In Patent Case Retrial Against Samsung, TECHCRUNCH, (November 21, 2013), … Continue reading Because of the new award, the total combined amount that Samsung needed to pay Apple decreased from $1.05 billion to $930 million. [67]Alan F., Samsung Seeks Retrial Of Retrial; Claims Apple Used Racial Tactics To Appeal To Jury, PHONE ARENA, (December 17, 2013,11.39) … Continue reading

On December 14, 2013, Samsung requested a Judgment as a Matter of Law (“JMOL”) and a new trial on the limited damages retrial. [68]Florian Mueller, Samsung wants a retrial of the November retrial in its first U.S. patent litigation with Apple, FOSS PATENTS, (December 17, 2013), … Continue reading

Apple v. Samsung II

While the first litigation was still pending and before trial had begun, Apple filed its second lawsuit against Samsung on February 8, 2012. [69]See generally Complaint for Patent Infringement, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. CV 12-00630 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 8, 2012). Apple asserted eight utility patents in its complaint, targeting Samsung’s other products in the market, such as the Galaxy S II and the Galaxy Nexus. [70]Complaint for Patent Infringement, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. CV 12-00630, at paragraph 16 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 8, 2012). Apple asserted the following patents in its complaint: U.S. Patent Nos. … Continue reading Samsung countersued with its own eight utility patents. [71]Samsung Defendant’s Answer, Affirmative Defenses, and Counterclaims to Apple Inc.’s Complaint; and Demand for Jury Trial, pp. 10 paragraph 1, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs., Co., No. … Continue reading Adding to its claims and as a countermeasure against Samsung’s assertion of its patents, Apple alleged fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”) antitrust counterclaims against Samsung. [72]Counterclaim-Defendant Apple Inc.’s Answer, Defenses, and Counterclaims in Reply to Samsung’s Counterclaims, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs., Co., No. 12-CV-00630-LHK, at paragraph 176-183 (N.D. … Continue reading

In April 2013, Judge Lucy Koh, who also presided over the second litigation, issued a case management order, requiring each party to limit their asserted patents to five per side and their accused products to ten per side by February 2014. [73]Case Management Order, Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 12-CV-00630-LHK, pp. 2 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2013).

Both parties quickly complied with the order and withdrew patents from their case. [74]See Florian Mueller, Apple Wants to Add Galaxy S4 to Second Patent Case Against Samsung in California (Spring 2014 Trial), Foss Patents, (May 14, 2013), … Continue reading By September 6, 2013, both sides had reduced their asserted patents to five patents each. [75]See Florian Mueller, Apple, Samsung Drop One Patent Each from Second California Case (Spring 2014 Trial), Foss Patents, (September 7, 2013), … Continue reading Additionally, Apple withdrew its FRAND antitrust counterclaims. [76]See Florian Mueller, Samsung Tries to Relitigate Pinch-to-Zoom Infringement, Apple’s Autocomplete Patent Reexamined, Foss Patents, (August 15, 2013), … Continue reading Apple’s remaining patents included the ‘647 patent (“data tapping”), [77]Patent pundits have given the ‘647 patent the nickname “data tapping.” Dan Rowinski, Apple’s ‘647 Patent: What It Is and Why It’s Bad for the Mobile Ecosystem, ReadWriteWeb, (June 13, … Continue reading the ‘959 patent (Siri-style unified search), the ‘414 patent (asynchronous data synchronization), the ‘721 patent (slide-to-unlock), and the ‘172 patent (autocomplete). [78]See Florian Mueller, Apple, Samsung Drop One Patent Each from Second California Case (Spring 2014 Trial), Foss Patents, (September 7, 2013), … Continue reading On the other side, Samsung had the ‘087 patent (non-scheduled transmission over enhanced uplink data channel), the ‘596 patent (signaling control information of uplink packet data service), the ‘757 patent (multimedia synchronization), the ‘449 patent (recording and reproducing digital image and speech), and the ‘239 patent (remote video transmission system) remaining. [79]Id.

On January 21, 2014, Judge Koh issued a partial summary judgment invalidating Samsung’s ‘757 patent (multimedia synchronization), and finding Samsung’s Android-based handsets to have infringed on Apple’s ‘172 patent (autocomplete). [80]Order Granting-in-Part and Denying-in-Part Apple’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment and Denying Samsung’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs., Co., No. … Continue reading With this partial summary judgment, Samsung had only four patents remaining in its counterclaim. [81]Id.

According to the case management order issued on April 24, 2013, the jury trial for the second litigation was scheduled to begin on March 31, 2014 with the trial set to conclude within twelve days. [82]Case Management Order, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 12-CV-00630-LHK, at pp. 2 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2013).

Preliminary Injunction

Filed with the complaint for Apple v. Samsung II, on February 8, 2012, Apple also filed a motion for preliminary injunction to enjoin Samsung’s Galaxy Nexus, asserting four patents. [83]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 877 F. Supp. 2d 838, 854 (N.D. Cal. July 1, 2012). In its motion, Apple requested the district court to stop the domestic sale of Samsung Galaxy Nexus, a smartphone co-developed by Samsung and Google. [84]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 877 F. Supp. 2d 838, 855 (N.D. Cal. July 1, 2012).

On July 1, 2012, Judge Koh granted the preliminary injunction, ruling that the Galaxy Nexus infringed on Apple’s ‘604 patent (Siri-style unified search). [85]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., 877 F. Supp. 2d 838, 918 (N.D. Cal. July 1, 2012). Samsung appealed the decision to the Federal Circuit and requested for a temporary stay on the injunction with both the district court and the Federal Circuit. [86]See Florian Mueller, Samsung Wins Temporary Stay of Galaxy Nexus Ban, Foss Patents, (July 6, 2012), http://www.fosspatents.com/2012/07/samsung-wins-temporary-stay-of-galaxy.html. The district court denied the stay, [87]See Florian Mueller, Federal Circuit Extends Stay of Samsung Galaxy Nexus Injunction — for the Time Being, Foss Patents (July 30, 2012), … Continue reading but the Federal Circuit granted the temporary stay in an order dated July 6, 2012. [88]Order, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 2012-1507 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The temporary stay allowed Samsung to temporarily continue selling the Galaxy Nexus. [89]Id.

In the October 11, 2012 decision, the Federal Circuit ruled that the district court abused its discretion and reversed and remanded the case back to district court. [90]Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 695 F.3d 1370, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The Federal Circuit found that the district court’s grant of a preliminary injunction was improper because there was no sufficient causal relationship between patent infringed (the ‘604 patent) and the consumer demand for the infringing product. [91]Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 695 F.3d 1370, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2012); see also, Florian Mueller, Federal Circuit Reverses Nexus Injunction for Lack of a Nexus and Doubts About Infringement, Foss … Continue reading The Federal Circuit also determined that Apple was not likely to prevail on infringement claim on the ‘604 patent because Apple had not identified all of potential heuristic modules in its claim construction. [92]Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 695 F.3d 1370, 1378-80 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

2. The United States International Trade Commission

The United States International Trade Commission (“ITC”) was another stage in the process of litigation where the superpowers asserted their dominance. [93]See, e.g., ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, Jun. 28, 2011; ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, July 5, 2011. Usually a forum for high-stakes intellectual property cases, the ITC has been favored by entities when resolving important disputes because of its expedited investigations and effective remedies. [94]Litigation – ITC Section 337 Patent Litigation, Finnegan, http://www.finnegan.com/ITCSection337PatentLitigationPractice/ (last visited Jan. 3, 2014). Generally, one may request the ITC to initiate a Section 337 investigation involving claims regarding intellectual property rights. [95]Intellectual Property Infringement and Other Unfair Acts, United States International Trade Commission, http://www.usitc.gov/intellectual_property/ (last visited Jan. 3, 2014). Additionally, the claims may include allegations of unlawful and unauthorized importation of goods that infringe on one’s patent or trademark. [96]Id.

The relief, which may be granted by the ITC, is a permanent exclusion order that directs Customs to prohibit entry into the United States of the infringing goods. [97]Id. Additionally, a permanent cease and desist order may be issued against entities engaged in unfair acts violating Section 337. [98]Id.

Samsung’s Complaint Against Apple

About two months after Apple had filed its lawsuit against Samsung in Apple v. Samsung I, Samsung chose to preemptively strike at Apple through the ITC forum. [99]ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, Jun. 28, 2011; see also, Eric Schweibenz & Alex Englehart, Samsung Files New 337 Complaint Regarding Certain Electronic Devices, Including Wireless Communication … Continue reading On June 28, 2011, Samsung filed a complaint to the ITC against Apple just a few days before Samsung filed its answer to Apple’s amended complaint in the first litigation. [100]ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, Jun. 28, 2011; see also, Eric Schweibenz & Alex Englehart, Samsung Files New 337 Complaint Regarding Certain Electronic Devices, Including Wireless Communication … Continue reading

In its investigation, which began on August 1, 2011, the ITC found that the alleged Apple products did infringe on one of Samsung’s cellular standard-essential patents (SEPs). [101]Limited Exclusion Order, ITC, Inv. No. 337-TA-794, June 4, 2013. Moreover, the ITC ordered in its decision a United States import ban against older iPhones and iPads (mainly iPhone 3, iPhone 4, iPad 1, and iPad 2). [102]Limited Exclusion Order, ITC, Inv. No. 337-TA-794, June 4, 2013; see also, Florian Mueller, ITC Bans Importation of Older Iphones and Ipads into the U.S. Over 3G-Essential Samsung Patent, Foss … Continue reading

In an effort to prevent such a ban from going into effect, Apple urged Obama and his Administration to veto the ban. [103]See Florian Mueller, Apple Urges United States Trade Representative to Toss iPhone, iPad Import Ban Won by Samsung, Foss Patents, (June 26, 2013), … Continue reading The United States Trade Representative (“USTR”), the representative for the Obama administration in dealing with presidential reviews of ITC exclusion orders, [104]Mission of the USTR, Office of the United States Trade Representative, http://www.ustr.gov/about-us/mission (last visited Jan. 3, 2014). disapproved of the ITC’s import ban on the older Apple products, expressing concerns related to the SEPs. [105]United States Trade Representative letter announcing the veto, available at http://www.ustr.gov/sites/default/files/08032013%20Letter_1.PDF; see also, Florian Mueller, Obama Administration Vetoes ITC … Continue reading The USTR therefore vetoed the Apple ban, effectively giving the first veto on an ITC ruling since 1987. [106]Connie Guglielmo, President Obama Vetoes ITC Ban on iPhone, iPads; Apple Happy, Samsung Not, Forbes, (August 3, 2013,9:40 p.m) … Continue reading

Apple’s Complaint against Samsung

Filed a week after Samsung’s complaint to the ITC, Apple’s complaint to the ITC asserted five utility patents and two design patents (U.S. Patent Nos. 7,479,949, 7,912,501, RE41,922, 7,863,533, 7,789,697, D618,678, and D558,757), targeting six Samsung smartphones and two tablets. [107]ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, July 5, 2011; see also, Eric Schweibenz & Alex Englehart, Samsung Files New 337 Complaint Regarding Certain Electronic Devices, Including Wireless Communication … Continue reading

As in the Samsung investigation, the ITC found Samsung to have infringed on two Apple patents (7,479,949 and 7,912,501). [108]U.S. ITC, No. 337-TA-796, In the Matter of Certain Electronic Digital Media Devices and Components Thereof (Aug. 9, 2013); see also, Mikey Campbell, Apple wins ITC ban on Samsung products [updated … Continue reading Additionally, and much to Apple’s disappointment, the investigation did not find infringement on two of the design patents (D618,678 and D558,757). [109]Id. On August 9, 2013, the ITC issued its initial determination, ordering an import ban on the offending products. [110]Id.

Hoping for a similar result as with Apple, Samsung also urged the USTR to disapprove the ITC determination within the 60-day presidential review period. To Samsung’s disappointment, the administration declined to do so, announcing on October 23, 2013 that the administration had approved of the ITC’s determination. [111]Ambassador Froman’s Decision on the USITC’s Investigation of Certain Electronic Digital Media Devices, October 8, 2013, Office of the USTR, available at … Continue reading

In an effort to broaden the import ban against Samsung, Apple filed an appeal on October 9, 2013 to the Federal Circuit appealing the unfavorable parts of the ITC ruling. [112]See Florian Mueller, Apple Seeks to Broaden U.S. Import Ban Against Samsung Through Federal Circuit Appeal, Foss Patents, (October 15, 2013), … Continue reading If the Federal Circuit rules in favor of Apple, the decision could potentially reverse the ITC’s ruling to allow for certain workarounds. [113]See id.

3. United States Patent and Trademark Office

Some of the battles between Apple and Samsung also occurred at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). Because the USPTO is the government entity that grants and issues patents, the USPTO is a logical place to challenge the validity of a patent. Typically a preferred venue for patent validity challenges over litigation due to its expertise in the technology area, the USPTO provides a process for patent review after issuance. [114]J. Steven Baughman, Reexamining Reexaminations: A Fresh Look at the Ex Parte and Inter Partes Mechanisms for Reviewing Issued Patents, 89 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 349, 350 (May 2007). Prior to the America Invents Act passed in 2012, one could challenge a patent by two methods: inter partes reexamination and ex parte reexamination. [115]Id. One key difference between the two methods was that ex parte reexamination allowed the challenger to submit a request anonymously. [116]Id.

In May 2012, the USPTO received anonymous requests for ex parte reexaminations on two of Apple’s patents asserted in Apple v. Samsung I: the ‘381 patent (rubber-banding) and the ‘949 patent (touchscreen heuristics). [117]See Florian Mueller, Apple’s Two Most Important Multitouch Software Patents Face Anonymous Challenges at the USPTO, Foss Patents, (May 29, 2012), … Continue reading Subsequently, an anonymous request for ex parte reexamination on the ‘915 patent (pinch-to-zoom API) was also filed. [118]See Florian Mueller, Tentatively Invalid: The Most Valuable Multitouch Patent Asserted by Apple at Samsung Trial, Foss Patents, (December 20, 2012), … Continue reading In October 2012, Apple received a first Office action rejecting all the claims for the ‘381 patent, [119]See Florian Mueller, Patent Office Tentatively Invalidates Apple’s Rubber-Banding Patent Used in Samsung Trial, Foss Patents, (October 23, 2012), … Continue reading and in December 2012, it received Office actions rejecting all the claims of the ‘949 patent and of the ‘915 patent. [120]See Florian Mueller, U.S. Patent Office Declares ‘The Steve Jobs Patent’ Entirely Invalid on Non-Final Basis, Foss Patents, (Dec. 7, 2012), … Continue reading In March 2013, Apple received a final Office action rejecting all but three of the claims of the ‘381 patent. [121]See Florian Mueller, Patent Office Confirms Three Claims of Apple’s Rubber-Banding Patent — But Not the Key One, Foss Patents, (April 2, 2013), … Continue reading

Seeking a stay on the damages retrial that was set to begin in November 2013, Samsung had repeatedly notified the court of the reexamination progress starting in April 2013. [122]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, Samsung Agrees with Apple That Judge Koh’s Appeal-Before-Retrial Plan Doesn’t Work, Foss Patents, (April 10, 2013), … Continue reading Samsung argued that since these patents are material to the limited damages retrial and their validity is in question, a stay on the retrial should be granted until the pending reexamination proceedings for the patents has ended. [123]See Kevin Krause, Samsung Requests Stay of Trial As USPTO Reexamines Apple’s Pinch-To-Zoom Patent, (April 18, 2013), http://phandroid.com/2013/04/18/samsung-apple-trial-stay-request/; see also, … Continue reading Unfortunately for Samsung, the district court denied Samsung’s motions to stay. [124]See, e.g., Case Management Order, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK (N.D. Cal. Apr. 29, 2013); see also, Florian Mueller, Judge Denies Samsung Motion to Stay Apple’s Patent … Continue reading In Judge Koh’s denial of Samsung’s motion for emergency stay that was filed on November 20, 2013, [125]See generally Samsung’s Emergency Renewed Motion for Stay Pending Reexamination of U.S. Patent No. 7,844,915, Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-cv-01846-LHK (PSG) (N.D. Cal. Nov. 20, 2013); … Continue reading she explained that “[f]urther delay of relief due to a stay of this entire case pending a final decision on the ‘915 patent would thus substantially prejudice Apple.” [126]Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK (N.D. Cal. Nov. 25, 2013).

In June 2013, Apple finally received notification from the USPTO of its intent to issue a reexamination certificate confirming four claims of the ‘381 patent. [127]See Florian Mueller, Huge Win for Apple at the Patent Office: Key Claims of Rubber-Banding Patent Confirmed, Foss Patents, (June 13, 2013), … Continue reading Fortunately for Apple, claim 19 was among the four claims upheld. [128]See id. Because claim 19 was successfully asserted in Apple v. Samsung I, the USPTO’s affirmation of claim 19’s validity through this reexamination process meant that Apple could claim damages for Samsung’s infringement on the claim. [129]See id.

In September 2013, the USPTO issued a certificate confirming patentability of all the claims of the ‘949 patent. [130]Bryan Bishop, Apple Multitouch Patent Upheld by US Patent and Trademark Office, The Verge, October 17, 2013, … Continue reading

As for the ‘915 patent, in July 2013, the examiner at the USPTO’s Central Reexamination Division rejected all the claims of the ‘915 patent in the final Office action. [131]See Florian Mueller, USPTO Hands Down Final (But Not Really Final) Rejection of Apple’s Pinch-to-Zoom API Patent, Foss Patents, (July 28, 2013), … Continue reading After arguing unsuccessfully that the ‘915 patent is valid in its response to the final Office action, Apple subsequently appealed that decision to the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) in December 2013. [132]See Florian Mueller, Impact Assessment of Apple’s Renewed Motion for U.S. Permanent Injunction Against Samsung, Foss Patents, (December 27, 2013), … Continue reading Through appeals, Apple could keep the patent alive until at least 2017. [133]See id. Apple has a strong interest in keeping the ‘915 patent alive as long as possible. As mentioned earlier, twelve of the thirteen Samsung products being retried were found to have infringed on this patent. [134]See Florian Mueller, USPTO Hands Down Final (But Not Really Final) Rejection of Apple’s Pinch-to-Zoom API Patent, Foss Patents, (July 28, 2013), … Continue reading

In December 2012, another anonymous ex parte reexamination request was filed against five claims of Apple’s RE41,922 patent. [135]See Florian Mueller, Reexamination Requested Against Another Apple Patent Samsung Was Found to Infringe, Foss Patents, (December 21, 2012), … Continue reading This patent, as mentioned above, was asserted by Apple in its ITC complaint and was found by the ITC to have been infringed by Samsung. [136]See, e.g., ITC, No. 337-TA-____, Complaint, July 5, 2011; see also, Eric Schweibenz & Alex Englehart, Samsung Files New 337 Complaint Regarding Certain Electronic Devices, Including Wireless … Continue reading

In regards to Apple v. Samsung II, as of June 2013, anonymous ex parte reexamination requests were filed concerning Apple’s ‘172 patent (autocomplete) and ‘760 patent (missed-call). [137]See Florian Mueller, Anonymous Reexamination Requests Filed Against Two More Patents Apple Is Suing Samsung Over, Foss Patents, (June 17, 2013), … Continue reading As discussed above, these two patents are among the eight asserted patents against Samsung. [138]See Florian Mueller, Apple, Samsung Drop One Patent Each from Second California Case (Spring 2014 Trial), Foss Patents, (September 7, 2013), … Continue reading

4. Cases Abroad

Despite all of the action within the national bounds of the United States, both Samsung and Apple pursued litigation in other jurisdictions throughout the world. The following descriptions are not intended to be fully inclusive of all international events. Rather, they are intended to give an indication of some of the international activity relating to the Apple and Samsung dispute.

In South Korea, the courts found that both Samsung and Apple infringed each other’s patents in a case filed in 2012. [139]See, e.g., Eric Abent, Apple and Samsung Both Infringe on Each Other’s Patents, Korean Court Rules, Android Community, (August 24, 2012), … Continue reading Furthermore, in a recent case, the courts dismissed Samsung’s claim of infringement on its patents related to messaging features, which is particularly noteworthy considering that Samsung’s own headquarters is in South Korea. [140]See, e.g., Juan Carlos Torres, Samsung loses to Apple in legal battle in own home turf, ANDROID COMMUNITY, (December 12, 2013), … Continue reading

In Germany, a German court in August 2011 granted Apple’s request of a preliminary injunction against the Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 for infringement on two Apple patents. [141]See Florian Mueller, Preliminary injunction granted by German court: Apple blocks Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 in the entire European Union except for the Netherlands, FOSS PATENTS, (August 9, 2011), … Continue reading The preliminary injunction was a ban that spanned the entire European Union (“EU”). [142]Id. Because Samsung was able to successfully show that Apple had engaged in evidence tampering, the court later changed the injunction, narrowing the effect from EU-wide to only the German market. [143]Chris Foresman, Apple stops Samsung, wins EU-wide injunction against Galaxy Tab 10.1, ARS TECHNICA, August 9, 2011, … Continue reading

Subsequently, on September 9, 2011, the German courts ruled in favor of Apple, finding that Samsung had infringed Apple’s patents. [144]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, Apple wins (again) in Germany: Galaxy Tab 10.1 injunction upheld, FOSS PATENTS, (September 9, 2011), … Continue reading A sales ban on the Galaxy Tab 10.1 was, therefore, issued. [145]See, e.g., Jason Mick, Apple Crushes Samsung in German Court, Galaxy Tab 10.1 Ban is Complete, DAILY TECH, (September 9, 2011), … Continue reading

In March 2012, another German court dismissed both the Apple and Samsung cases relating to ownership of the “slide-to-unlock” function. [146]See, e.g., Harriet Torry and Ian Sherr, German Court Dismisses Samsung, Apple Patent Suits, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, (March 2, 2012), available at … Continue reading In July 2012, the Munich Higher Regional Court Oberlandesgericht München, in affirming the lower Regional Court’s decision, denied Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction relating to Apple’s “rubber-banding” patent, and in a separate ruling, found the patent to be possibly invalid. [147]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, One Munich court denies an Apple injunction motion, another tosses a Microsoft lawsuit, FOSS PATENTS, (July 26, 2012), … Continue reading On September 21, 2012, the Mannheim Regional Court found that Samsung did not infringe Apple’s patents regarding touch-screen technology. [148]See, e.g., Jun Yang and Karin Matussek, Apple Loses German Court Ruling Against Samsung in Patent Suit, BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK, (September 21, 2012),available at … Continue reading

In November 2013, eight hours after the verdict of the damages retrial of Apple v. Samsung I, the Mannheim Regional Court issued a stay on the pending litigation between Samsung and Apple. [149]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, German court stays Samsung patent lawsuit against Apple: patent of doubtful validity, FOSS PATENTS, (November 22, 2013), … Continue reading The court indicated that infringement had been found, but doubted the validity of Samsung’s European patent. [150]Id.

In the United Kingdom, Samsung brought suit against Apple and prevailed, with the court finding that “Galaxy tablets aren’t “cool” enough to be confused with Apple[]’s iPad.” [151]Kit Chellel, Samsung Wins U.K. Apple Ruling Over ‘Not as Cool’ Galaxy Tab, BLOOMBERG TECHNOLOGY, (July 9, 2012), … Continue reading Later, Apple was ordered to publish a disclaimer on its website indicating that Samsung did not copy the iPad. [152]Eric Ravenscraft, UK Judge Orders Apple To Publicly State On Its Website That Samsung Didn’t Copy The iPad, ANDROID POLICE, … Continue reading

Additionally, in Japan, Samsung and Apple both brought separate cases of patent infringement. [153]See, e.g., Jun Yang, Samsung Sues Apple on Patent-Infringement Claims as Legal Dispute Deepens, BLOOMBERG TECHNOLOGY, (April 21, 2011), … Continue reading Notably, Apple filed one suit specifically on the “bounce-back” feature. [154]See, e.g., Ida Torres, Tokyo Court rules in favor of Apple over ‘bounce-back’ patent, JDP, (June 21, 2013), … Continue reading The Tokyo Court ruled in favor of Apple over the “bounce-back” feature patent, but found that Samsung did not violate Apple’s patents on technology that synchronizes music and videos. [155]See, e.g., id; see also, Hiroko Tabuchi and Nick Wingfield, Tokyo Court Hands Win to Samsung Over Apple, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (August 31, 2012), … Continue reading

Lastly, in the Netherlands, Apple initially sued Samsung, and on October 24, 2011, the Hague court found in Apple’s favor, resulting in an import ban against Samsung. [156]See, e.g., Lex Boon, Rechtbank Den Haag verbiedt smartphones Samsung – ‘Apple delft onderspit’, NRC.NL, August 24, 2011, … Continue reading However, the import ban concerned only specific Android devices running infringing software. [157]Id. As such, the import ban was narrowly focused. [158]Id. Apple appealed the decision. The Dutch appellate court determined on January 24, 2012 that Samsung’s Galaxy Tablet did not infringe Apple’s patent. [159]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, Dutch appeals court says Galaxy Tab 10.1 doesn’t infringe Apple’s design right, FOSS PATENTS, (January 24, 2012), … Continue reading

On September 26, 2011, Samsung requested the Hague court for an injunction against Apple’s products based on standards-essential, FRAND patents. [160]See, e.g., Mike Corder, Samsung seeks iPhone, iPad sale ban in Dutch court, AP WORLDSTREAM, (September 26), 2011, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1A1-84e50e08c6c545a69eafc8fc1c714bd9.html. The Hague court responded on October 14 and denied Samsung’s request. [161]See, e.g., Florian Mueller, Samsung loses Dutch case against Apple over 3G patents as court gives meaning to FRAND, FOSS PATENTS, (October 14, 2011), … Continue reading

Part II: Repercussions of Apple v. Samsung

We have thus far reviewed the procedural aspects of the Apple v. Samsung dispute. Part II will now analyze the repercussions of the case. [162]When referring to “the case” or “Apple v. Samsung,” it should be understood that the combination of all of the procedural events and cases are included despite the pronouns or case being in … Continue reading

At the outset, scrutinizing the repercussions should not be construed as a standard tort-law “proximate cause” analysis. [163]See, e.g., Robin Meadow, Proximate Cause: A Question of Fact or Policy?, ASSOCIATION OF BUSINESS TRIAL LAWYERS REPORT 22(2), 5 (2000) (“Recall that Palsgrafs problems began when a railroad guard … Continue reading To say that “but for” the Apple v. Samsung case occurring, the following repercussions would not have occurred, would be a naïve view on the overall patent landscape. Apple v. Samsung is not the only case – and not the only event – that has garnered public interest and attention. [164]See, e.g., Thomas H. Chia, Fighting the Smartphone Patent War with RAND-Encumbered Patents, BERKELEY TECH. L.J., Vol: 27, 209, 213 (2012) (“Due to the escalation in patent infringement suits in the … Continue reading

However, just as a rock thrown in a pool of water creates ripples, the Apple v. Samsung case, at a minimum, has created some ripples. It may not be the only source of ripples in the pond, but it definitely has created such significant interest – and scrutiny – that it warrants a careful analysis. Notwithstanding such a disclosure, the possible consequences of this case will now be considered.

1. General Perception of Patents

Reporters have described the Apple v. Samsung case as the “[t]he patent trial of the century.” [165]See, e.g., Seth Fiegerman, Apple Vs. Samsung: Everything You Need To Know About The (Patent) Trial Of The Century, BUSINESS INSIDER, (July 30, 2012), available at … Continue reading That is a rather extreme description, considering that the last 50 years alone has provided the following notable cases:

| Case | Court | Year | Conclusion |

| Graham v. John Deere Co. [166]Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966). | Supreme | 1966 | Clarified the requirements of non-obviousness |

| Diamond v. Chakrabarty [167]Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980). | Supreme | 1980 | Found that genetically micro-organisms are patentable |

| Diamond v. Diehr [168]Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981). | Supreme | 1981 | Found that a machine which transforms materials physically under the control of a programmed computer is patentable |

| Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc. [169]Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 517 U.S. 370 (1996). | Supreme | 1996 | Found that claim interpretation was a matter of law |

| State Street Bank v. Signature Financial Group [170]State Street Bank and Trust Company v. Signature Financial Group, Inc., 149 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1998). | CAFC | 1998 | Found that that business methods could be patented |

| KSR v. Teleflex [171]KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007). | Supreme | 2007 | Clarified reasoning for obviousness |

| Bilski v. Kappos [172]Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. ___ (2010). | Supreme | 2009 | Found that the machine-or-transformation test is not the sole test for determining patent eligibility |

Interestingly, although the listed cases give some indication of the evolving nature of patent law, Apple v. Samsung does not necessarily clarify or add a new insight into patent law. [173]Further appellate action by Apple or Samsung may give additional teaching relating to core patent law concepts. In fact, unlike many of these cases which resolved some patently ambiguous defect in the patent system, the Apple v. Samsung case has remained focused on a basic issue of patent infringement. [174]It is noted that almost any patent case started at one level as some type of patent infringement. That being said, however, many of the notable patent cases include examples where a defect was found … Continue reading The question, therefore, arises as to why this case has achieved such notoriety. [175]See, e.g., Patrick A. Doody, Patents and Business: 9 Trends to Expect This Year, LAW 360, (January 14, 2013), http://www.law360.com/articles/405091/patents-and-business-9-trends-to-expect-this-year … Continue reading

At one level, possibly this case has struck a chord with the general public. Everyone has seen an Apple or Samsung device. And the reality is that as much as 68% of the general public owns one. [176]See, e.g., Brian X. Chen, Apple and Samsung Widen Lead in U.S. Phone Market, THE NEW YORK TIMES BITS, (January 16, 2014), … Continue reading Additionally, these devices are not seen as some obscure technology or remote process – it is technology that is seen day-to-day. Perhaps the pragmatic nature of the technology combined with the ubiquitous nature of the devices has increased the attention of the general public.

Notwithstanding the familiarity with the device, this case, at a minimum, emphasizes the complexity of patents – and its relation to the common man. Rather than have these complicated patents analyzed and interpreted by technical scientists, they are examined, and damages are allocated by a jury composed of everyday individuals. [177]See, e.g., Jennifer F. Miller, Should Juries Hear Complex Patent Cases?, 2004 DUKE L. & TECH, REV. 4 (2004) (“With the rise in both the complexity and the importance of patent infringement … Continue reading At a minimum, therefore, this case emphasizes the burden the common juror faces in evaluating complex patents in a patent infringement case.

As an example, U.S. Patent Number 7,698,711 was asserted by Samsung in the case at issue. [178]See, e.g., Ryan Davis, Judge Punts On Apple’s Bid To Bar Samsung SEP Claims, LAW 360, (December 13, 2012), http://www.law360.com/articles/401477 (“The Apple patents-in-suit are U.S. Patent … Continue reading Claim 1 provides:

A multi-tasking method in a pocket-sized mobile communication device including an MP3 playing capability, the multi-tasking method comprising:

generating a music background play object, wherein the music background play object includes an application module including at least one applet;

providing an interface for music play by the music background play object;

selecting an MP3 mode in the pocket-sized mobile communication device using the interface;

selecting and playing a music file in the pocket-sized mobile communication device in the MP3 mode;

switching the MP3 mode to a standby mode while the playing of the music file continues;

displaying an indication that the music file is being played in the standby mode;

selecting and performing at least one function of the pocket-sized mobile communication device from the standby mode while the playing of the music file continues;

and continuing to display the indication that the music file is being played while performing the selected function.

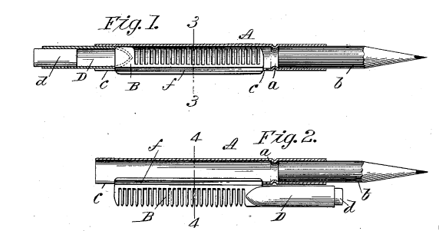

Reading the claim alone may feel like a complex grammar lesson or a mind exercise at keeping each introduced element straight – it is simply not easy. Some may argue that patents were not always complex. However, even a relatively basic invention, such as the comb-pen from 1898 [179]U.S. Pat. No. 605,674. , can seem complex:

[180]Id.

[180]Id.

The foregoing invention was claimed as:

[]a new article of manufacture a combined pencil-case and comb-case comprising a pencil-holding tube adapted to receive at one end a pencil, and provided with a longitudinal slot extending part way the length of the tube from the opposite end thereof, and a reversible comb having a longitudinally-grooved back which fits in, and engages the edges of, the slot in the pencil-holding tube, and can slide back and forth therein, and provided with an end tube or plug adapted to fit the end of the pencil-tube to which the comb is applied. [181]Id.

To a person who reads patents constantly, the foregoing claim is straight forward and clear. However, claim language is simply not normal speech. It is very formulaic, and given the drafter’s ability to be a lexicographer [182]See, e.g., Interpreting the Clams, M.P.E.P. § 2173.01 (“A fundamental principle contained in 35 U.S.C. 112, second paragraph is that applicants are their own lexicographers. They can define in the … Continue reading , the terms can be defined in any manner [183]See, e.g., id. at 2173.05(a)(III) (“Consistent with the well-established axiom in patent law that a patentee or applicant is free to be his or her own lexicographer, a patentee or applicant may use … Continue reading .

In view of this, one can conclude that even with relatively straight forward and simple inventions, patents and patent claims can still appear complex, especially to a common person juror.

A second conclusion may be taken from this case: high damages may not correlate with public attention. For example, the following table [184]Margaret Cronin Fisk, Largest U.S. Jury Verdicts of 2012, BLOOMBERG NEWS, (January 17, 2013), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-18/largest-u-s-jury-verdicts-of-2012-table-.html. lists the top patent verdicts from 2012:

| Case | Amount of Verdict |

| Carnegie Mellon University v. Marvell Technology Group Inc. | $1.17B |

| Apple v. Samsung | $1.05B |

| Monsanto v. DuPont | $1.00B |

| Virnext v. Cisco | $368M |

Interestingly, the Apple v. Samsung case was not the highest patent verdict for the year 2012. [185]Id. It was, in fact, the second highest verdict for 2012. [186]Id. Carnegie Mellon University’s case was the highest patent verdict of the year and arguably one of the highest patent verdicts of all time. [187]See e.g., Ben Kersey, Marvell hit with $1.17 billion damages verdict in patent infringement case, THE VERGE, (December 27, 2012), … Continue reading Based off of this high verdict, one would expect the Carnegie Mellon case to garner the attention of the general public. However, the lack of congruity between the amount of verdict and public interest may relate to factors beyond the mere amount of recovery, including for example, the technology of the patent, as well as the intended market target, as illustrated in the following table:

| Case | Technology [188]Margaret Cronin Fisk, Largest U.S. Jury Verdicts of 2012, BLOOMBERG NEWS, (January 17, 2013), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-18/largest-u-s-jury-verdicts-of-2012-table-.html. | Market Target |

| Carnegie Mellon University v. Marvell Technology Group Inc. | Integrated circuits | High Technology |

| Apple v. Samsung | Smartphone | Smartphone Industry |

| Monsanto v. DuPont | Herbicide-tolerant soybeans | Farming Industry |

| Virnetx v. Cisco | virtual-private-network | High Technology |

Viewing the top patent recoveries for 2012 through this lens gives a different perspective on potentially what attracts public attention. [189]Defining “public attention” is presumably somewhat of a subjective study (e.g. selecting the appropriate database, defining the target market segment, etc.). For purposes of this article, … Continue reading For example, the closer the technology of the patent relates directly to the general public (as described by the market target), the greater the probability that the case will interest the public.

In this case, the technology of the Carnegie Mellon University limited its level of attraction to the high technology market. Although the common person uses integrated circuits on a daily basis, the end device (e.g. a computer or tablet) was not something involved in the case Therefore, it did not generate general public interest. Contrast this with the Apple v. Samsung case, which concerned a smartphone and targeted the smartphone industry, which, arguably, could include nearly every person in the United States.

This pattern is followed with the following two cases as well. The Monsanto case did not generate interest that concerned the general public, but did generate considerable interest within the farming industry as the dispute related to something that could affect their day-to-day activities. [190]See, e.g., Puck Lo, Monsanto Bullies Small Farmers Over Planting Harvested GMO Seeds, Nation of Change, (Mar. 30, 2013), … Continue reading Further, the Virnext case did not generate much public interest, as again, the technology was not something that would directly affect the general public.

The Apple v. Samsung case illustrates, therefore, that the technology concerned and the targeted market involved directly influence the level of public attraction. Further, the closer the technology relates to the general target market, the greater the public attention.

2. International Significance

The turn of the 20th century brought rapid changes and expansion. Man could travel quicker by means of vehicles. [191]See, e.g., Eric Morris, From Horse Power to Horsepower, ACCESS 30, 2, 8 (Spring 2007) (“Enticed by high speeds, point-to-point travel and the flexibility to roam across the urban landscape, the … Continue reading Quality of life was improved through electricity and the light bulb, and communication was enhanced through the telephone. [192]See, e.g., Jeffrey, Phillip, Telephone and Audio Conferencing: Origins, Applications and Social Behaviour; unpublished manuscript, GMD FIT, (May 1998), available at … Continue reading It was indeed an era of rapid innovation and improvement. However, much of the world remained disparate and isolated. That changed in part with Charles Lindbergh, and later by Amelia Earhart, who proved that distances between countries could be crossed – in less than even a day. [193]See, e.g., “History,” Charles Lindbergh: An American Aviator, Spirit Of St. Louis 2 Project, available at http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/paris.asp; “Biography,” Amelia Earhart: The … Continue reading

Since that time, connections have expanded and isolated boundaries have dissolved. The world, which once was isolated and separated, has been replaced by international relations and trade. Today, the flow of products and material are truly on a global scale. [194]See, e.g., Michael D. Intriligator, Globalization Of The World Economy: Potential Benefits And Costs And A Net Assessment, 33 (Milken Institute, Policy Brief, 2003) (“Globalization has had … Continue reading

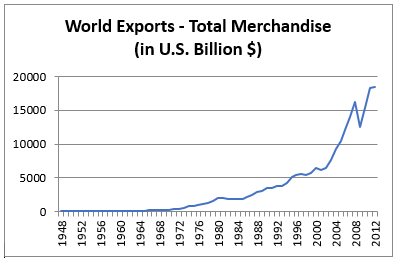

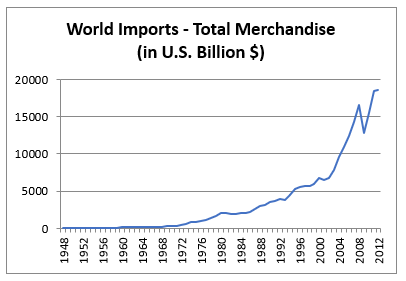

Using data from the World Trade Organization, the following charts illustrate total merchandise exports and imports in U.S. Billion dollars since 1948. [195]Compiled with data provided by the World Trade Organization, available at http://stat.wto.org/StatisticalProgram/WSDBStatProgramHome.aspx?Language=E. Although the charts illustrate an obvious increase, the greatest rise has visibly occurred over the past ten years. [196]Id.

Based on these figures, it is evident that individual countries and continents are exchanging ideas and products on a much more global scale than ever before.

The Apple v. Samsung case is no different than the current global trade phenomenon. The conflict is not limited solely to one jurisdiction or country, but it has spanned at least ten countries over more than three years. [197]See, e.g., Vincent LoTempio, The Impact of the Apple-Samsung Patent Wars, The Manzella Report, (July 6, 2013), … Continue reading Because this is an international conflict, and because a patent’s rights extend only to a limited jurisdiction, the reality is simply that both Samsung and Apple have patent rights in many countries around the world.

This is evidenced by a number of international events which relate to the U.S. based Apple v. Samsung case. For example, in 2011, Samsung received a European injunction against the Galaxy Tab, as part of its patent infringement lawsuit in Europe. [198]See, e.g., Chris Foresman, Apple stops Samsung, wins EU-wide injunction against Galaxy Tab 10.1, Ars Technica, (Aug. 9, 2011, 2:30 PM), … Continue reading Apple later won that infringement case and was successful in receiving a permanent sales ban on Samsung. [199]See, e.g., Mikael Ricknäs, Apple Wins Permanent Ban on German Sales of Samsung Tablet, TechHive, (Sept. 9, 2011, 3:30 AM), … Continue reading In a similar manner, the Netherlands court ruled that Samsung had infringed Apple Patent EP 2,059,868, but also found that Samsung did not infringe two of Apple’s other patents. [200]See, e.g., Zach Honig, Netherlands judge rules that Samsung Galaxy S, S II violate Apple patents, bans sales (updated), Endgadget, (Aug. 24, 2011, 9:22 AM), … Continue reading Across the channel, the U.K. court ruled that Samsung did not infringe Apple’s designs. [201]See, e.g., Zack Whittaker, Apple slams Samsung on its U.K. website after court ruling, ZDNet, (Oct. 26, 2012, 8:47 GMT), … Continue reading

Asia too has seen its share of Apple v. Samsung battles. Japan’s court found that Samsung did not violate Apple’s patent, whereas South Korea’s court delivered a split decision, finding that Apple infringed two of Samsung’s patents and that Samsung infringed one of Apple’s patents. [202]Tabuchi and and Wingfield, supra note 156; see also, Christina Bonnington, South Korean Court Rules Apple and Samsung Both Owe One Another Damages, WIred, (Aug. 24, 2012, 2:37 PM), … Continue reading

From an international perspective, therefore, the rulings and decisions have indicated anything but harmony and consistency. This is perhaps a direct reflection of the nature of patents themselves – their powers are limited to territories. And each territory may logically grant different patent claims, and may provide varying levels of rights to the patent holder. [203]See, e.g. “Patent Laws Around the World,” Patent Lens, available at http://www.patentlens.net/daisy/patentlens/ip/around-the-world.html (“A patent is awarded by the government of a country and … Continue reading

Beyond the differences in patents and patent rights, the nature of the courts also may influence the result. For example, juries [204]Tabuchi and Wingfield, supra note 156 (“Some law professors who have studied international patent disputes say the outcome of that case may be unique in the global tussle between the two companies. … Continue reading , damages [205]See, e.g, Toshiko Takenaka, Patent Infringement Damages in Japan and the United States: Will Increased Patent Infringement Damage Awards Revive the Japanese Economy?, 2 Wash. U. J. L. & Pol’y … Continue reading , and how software patents are treated by the courts [206]Many countries award copyrights for software-related inventions, which automatically include international protection (e.g. through the Berne Convention, etc.). The United States expressly … Continue reading may greatly influence the outcome of the case.

From a hypothetical micro perspective, such differences between countries in patents, patent rights, and courts may be slight. However, much as a three inch switch point ultimately determines a train’s destination (many times hundreds of miles apart in possibilities), minor patent variances can cause extremely significant dissimilarities. In view of such a situation, some legal scholars have promoted the notion of creating an international IP court to harmonize patent rights globally. [207]See, e.g., Allison Cychosz, The Effectiveness of International Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights, 37 J. Marshall L. Rev. 985, 1013 (2004) (“This Comment proposes that a specialized … Continue reading Although the feasibility of such a court will not be discussed in this paper, an international IP court highlights, at a minimum, the need for a court to address the wide gamut of differing patent rights.

While the above analysis highlights the individual nature and autonomy of each territory’s allocation of patent rights, it should be remembered that time continues to build greater relationships and worldwide connections. As such, due to the increasingly inter-connectedness of all countries, each country’s action with respect to patent rights may have some repercussion on the market and conditions in other countries.

For example, in 2013, Samsung and Apple filed requests with the International Trade Commission. [208]See, e.g., Derek Scissors, Apple vs. Samsung: Why Is the Obama Administration Involved?, The Foundry, (Aug. 13, 2013, 2:27 PM), … Continue reading The ITC in turn found that both Apple and Samsung infringed the other’s patents. [209]Id. Interestingly, however, while the Obama administration vetoed the ban on Apple products, it decided to maintain the ban on Samsung products. [210]Id.

Choosing to veto an ITC ban would presumably be the result of serious consideration and insight. In fact, the veto of the ITC ban for Apple was the first time a President administered this right since 1987. [211]See, e.g., Don Reisinger, President Obama declines to veto ban on Samsung products, CNET, (Oct. 8, 2013, 7:37 PM), … Continue reading The reasoning for vetoing the ban was because of Apple’s “effect on competitive conditions in the U.S. economy and the effect on U.S. consumers.” [212]Nick Gray, Apple Wins Again – Obama vetoes ITC’s US import ban on iPhones and iPads, Android and Me, (Aug. 3, 2013, 3:30 PM), … Continue reading

To a certain extent, selecting to veto one ban but very shortly afterwards denying to veto another ban, sends a signal of favoritism. Apple – an American-based company – received the veto. And Samsung – a Korean-based company – was denied the veto. In short, American-based companies may receive preferential treatment, while foreign-based companies may not. [213]See, e.g., Richard Waters, Obama overturns Apple import ban, Tech Hub, (Aug. 3, 2013), http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7321bf0a-fc6b-11e2-95fc-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2qcklCj9E (“‘It could be viewed as … Continue reading

On one hand, this idea of favoritism may work counter to the thrust of global expansion and interconnectedness. For example, rather than having countries come together to protect IP rights, favoritism may cause isolationism, where in order for companies to survive globally, countries are forced to give an ”edge-up” to such companies. If one company has a competitive advantage through the influence of government action, it would only make sense that a competitor would receive a similar competitive advantage in another company to balance out the competition.

This idea of favoritism may work to the benefit – or detriment – of the United States. As an example, having a more isolated country-against-country perspective may result in more companies to be based in the United States if they know they can receive preferential treatment. However, if the United States begins to more aggressively give preferential treatment, it can be assumed that other countries will increasingly grant preferential treatment as well. In short, rather than the laws of economics dictating competition between IP competitors, third party influences by government action may disrupt the “invisible hand” of a free market economy. [214]See, e.g., “Adam Smith,” The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, 2nd edition, available at http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Smith.html (“In Adam Smith’s lasting imagery, ‘By directing … Continue reading The greater the action, the greater the upset to “laissez-faire” conditions. [215]See, e.g., Emma Rothschild, “Economic Sentiments,” Harvard University Press, Feb 4, 2013, p. 30 (espousing the notion that laissez faire economics must be combined with political conservatism).

Furthermore, favoritism may cast the United States as a hypocrite, since, in recent years, the US has “made respect for intellectual property rights a cornerstone of its trade policy.” [216]Waters, supra note 214. In 2013, Senator Hatch proposed a bill to “help guarantee strong IP standards are upheld and enforced with global trading partners.” [217]“Hatch Announces Bill to Guarantee Strong IP Standards for U.S. in Global Trading System,” press release, Senate Committee on Finance, (Mar. 26, 2013), available at … Continue reading Interestingly, the bill sought to:

help guarantee that America remains at the forefront of innovation policy, that [America’s] trade agreements reflect the critical importance of intellectual property to [its] economy and that the preservation of high-standard IP protection and enforcement are at the forefront of every trade debate. [218]Id.

Such a focus would definitely help promote a global IP attitude. However, favoritism may dilute the power of these ambitions. Therefore, in order to truly endorse and encourage a worldwide IP agenda, the US must align its actions with what it is indicating is its focus.

A last issue here relates to an international view. The Apple v. Samsung case is far from being resolved. In fact, delays in the judicial process may prevent this from being completed anytime in the near future. [219]Bonnington, supra note 203 (“Apple plans to file a temporary injunction against Samsung’s infringing products. If granted, Apple could ban its key competitor from the market for months, if not … Continue reading Once the district court level process is complete, it can be assumed that the case will be appealed to the Federal Circuit (which alone could take at least another year and a half), as well as eventually to the Supreme Court. [220]See, e.g. id. Resolution, therefore, of the complete process requires significant time, which also translates into a substantial amount of money.

The process in the United States clearly indicates to the global arena that although high damages could be awarded, a final resolution may not occur for many years. [221]This is unlike other jurisdictions. For example, German patent litigation proceedings generally proceed at a quick pace (and can also achieve resolution in a shorter amount of time), and also … Continue reading So in the fight for high damages, companies can also count on a drawn-out, expensive legal battle.

Notwithstanding the differences in resolution between countries, one conclusion can be made: America’s slow judicial process may cause companies to seek restitution in other countries. The reality, however, is that companies will likely continue to seek restitution in all pertinent countries, taking a shotgun approach to mediation to increase the chances of success.

3. Litigation Considerations

In the prior section, forum and damages considerations were analyzed with respect to their influence internationally. This section will analyze similar and other effects of litigation within the United States.

Choice of Forum

As in any litigation suit, the choice of forum is one of the first questions considered. Given the large number of district courts in the country – and seemingly different actions and rulings in each district – the plaintiff may essentially forum shop to find the best district for the case. [222]See, e.g., Alisha Kay Taylor, What Does Forum Shopping in the Eastern District of Texas Mean for Patent Reform?, 6 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 570, 571 (2007) (“Patent cases are not evenly … Continue reading

There are many factors that go into selecting the right forum. Professor Lemley’s 2010 study concluded that, at a minimum, such factors may include: (1) likelihood of winning; (2) likelihood of getting to trial; and (3) speed of getting to trial. [223]Lemley, Mark A., Where to File Your Patent Case, AIPLA QUARTERLY JOURNAL Vol. 38(4), 1 (Fall 2010). For plaintiffs, they generally want a high likelihood of winning, a high likelihood of getting to trial, and a quick resolution. [224]Id. at 4. Conversely, defendants generally desire the exact opposite. [225]Id.

Further, in addition to the strategic balancing of these factors, the parties must comply with the federal rules of ensuring proper jurisdiction wherever the forum is selected. And, when patent litigation specifically is concerned, almost any jurisdiction could work based on “minimum contact” or “stream of commerce” theories. [226]William J. Brutocao, Personal jurisdiction and venue in US patent litigation, PATENT WORLD, Issue 189, 18 (February 2007) (“Many litigators assume that the law regarding personal jurisdiction … Continue reading

As such, the question therefore arises, out of all of the courts in the country, why did Apple initially select the Northern District of California as the forum?

Taking a step back, it helps to put the Apple v. Samsung case in context of other events. For example, beginning in 2010, Apple was involved in numerous lawsuits with Motorola all around the country, including the following districts: Northern District of Illinois [227]See, e.g., Chris Foresman, Motorola asks ITC, two federal courts to throw book at Apple, Ars Technica, (Oct. 6, 2010, 4:10 PM), … Continue reading , Southern District of Florida [228]See, e.g., id. , Delaware [229]See, e.g., Philip Elmer-DeWitt, Apple v. HTC: What’s the deal with Delaware?, CNN Money, (Oct. 2, 2010, 2:37 PM), … Continue reading , and the Western District of Wisconsin [230]Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc. and Motorola Mobility, Inc., 3:2011cv00178 (W.D.Wisc. Oct. 29, 2010). . And on top of this array of suits, patent smartphone wars were well under way. [231]See, e.g., Thomas H. Chia, Fighting the Smartphone Patent War with RAND-Encumbered Patents, BERKELEY TECH. L.J., Vol: 27, 209, 213 (2012) (“Due to the escalation in patent infringement suits in the … Continue reading Apple was therefore heavily involved in lawsuits across the country.

In view of this, perhaps Apple wanted to bring a case back home to its own headquarters to simplify the litigation abroad. Alternatively, Apple may have chosen the Northern District of California for a multitude of other reasons. For example, litigating a suit from the location where the company is headquartered may indirectly provide some ancillary favoritism. [232]Consider, for example, jury members from the Northern District who will be selected, and will, most likely, probably own at least one Apple product or at least be keenly aware of them. Or, fighting a war based from home may give a kinder public image of the company – an image of a company having been severely wronged, even on its own home turf, and is now seeking to be redressed. Whatever the reasons, Apple chose the Northern District of California and it worked out well for them thus far.

The next question is whether Apple, in choosing the Northern District of California, caused any repercussions across the country.

As some background, the Northern District of California was selected in 2011 to be included as one of the “patent pilot program” centers in the country. [233]See, e.g., Rader, Randall R., Addressing the Elephant: The Potential Effects of the Patent Cases Pilot Program and Leahy-Smith America Invents Act,” AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 62(4), 1105, … Continue reading This inclusion coincides with the Northern District of California’s long-time focus on patents. [234]See, e.g., James Ware and Brian Davy, The History, Content, Application And Influence Of The Northern District Of California’s Patent Local Rules, SANTA CLARA COMPUTER & HIGH TECH. L.J., Vol. … Continue reading

At one level, the Northern District of California has received considerable attention through its involvement with Apple v. Samsung. Although such attention may cause other districts to scrutinize their actions more, potential patent litigation plaintiffs may view the district as a more competent forum, simply because it is “the” forum associated with the Apple v. Samsung case.

Additionally, plaintiffs may be attracted to the forum based off of the initial damages Apple was awarded. These initial damages may create an unrealistic expectation of what other potential plaintiffs may be entitled. Consequently, along with a rise of potential plaintiffs, the district can also expect an increase in idealistic, but not pragmatic, expected damages.

Interestingly, despite its popularity with patent filings, the Northern District of California is also noted as one of the slowest jurisdictions in the country for final resolution. [235]See, e.g., Lemley, Mark A., Where to File Your Patent Case, AIPLA QUARTERLY JOURNAL Vol. 38(4), 1, 16 (Fall 2010) (“Interestingly, the Eastern District of Texas is among the slowest jurisdictions, … Continue reading Perhaps it is precisely this popularity which has caused a backlog of patent cases. [236]See, e.g., id. Thus, although the number of patent litigant filers may rise, this may be offset (i.e. net balance remains equal) by the influence of the increase in time required to reach final resolution, which may cause current and future patent litigant filers to look to other forums for resolution.

Litigation Costs

Litigation is not cheap. The attorneys, the damages, the time considerations, and the public image all contribute to a very expensive process.